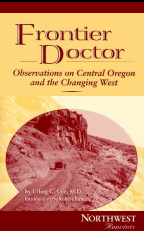

Frontier Doctor

Urling C. Coe

Introduction by Robert Bunting

In January 1905 Urling C. Coe moved to the new town of Bend, Oregon, to become the first licensed doctor in what he called "the heart of the last pioneer stock country of the West."

Frontier Doctor, Coe's autobiographical account of his thirteen-year residency, details the extraordinary experiences of a young physician in frontier Oregon, from childbirthing to epidemics, broken bones to unwanted pregnancies. Coe's colorful, first-hand stories about treating patients--cowboys, rustlers, ranch wives, Indians, prostitutes, homesteaders, and town boosters--offer a vivid social history of town and ranch life on the Oregon high desert. They also document the development of a Western boomtown: with the arrival of the railroad in 1911, the wide-open settlement known as Farewell Bend was transformed into an important center of industry, commerce, and culture.

In a new introduction Robert Bunting shows how Coe's informed opinions and observations illustrate themes prevalent in our own understanding of western history: the central role of women in the western experience, the significance of the urban West, the boom and bust nature of resource-dependent communities, concern for conservation, and Westerners' ambivalent relationship with the federal government. Northwest readers will find Coe's comments about the management of eastside forests especially relevant.

About the author

Urling C. Coe, M.D. (1881-1956) was born in Missouri and graduated from the University of Missouri and the Eclectic College of Cincinnati. He practiced medicine in Bend, where he also served as a banker and the town's second mayor, until 1918, when he moved to Portland. Frontier Doctor was originally published in 1940 by The MacMillan Company.

Read more about this author

Foreword

Here's a Doctor at Farewell Bend

Chapter

- Wide Open Town: I Arrive

- Doctor to Buckaroos

- Wild West Babies

- Epidemic on the Frontier

- Delivery by Telephone

- My First Death

- Teeth Extracted-$1

- Accidents and Indians

- Prostitution on the Frontier

- The Worst Enemy is Ignorance

- Horse Thieves and Cattle Rustlers

- Mr. and Mrs. --and the Doctor

- Complaints Real and Imaginary

- Ills and Bills

- Busman's Holiday

- Homestead and Forest

- The Doc as Mayor

- Pain and Pretense

- The Golden Spike

Urling C. Coe arose from a hotel room in Bend, Oregon, on January 10, 1905, to begin the first full day of his 13-year residence in this newly established Central Oregon town. Coe was a physician who became a leader in creating Bend's first hospital, a bank organizer and president, real estate dealer, and town mayor, and his recollections bring a reader into the world of medicine, town building, and life in Central Oregon, as well as to the larger contours of American society at the turn of the century. In the process, Coe touches on traditional themes of western history--openness, opportunity, individual heroics, farm and ranch life--as well as showing the West as a colonial hinterland dependent on outside capital investment, natural resource extraction, and the federal government. But here, too, are the newer topics in western history such as conservationism, environmental change, the urban West, women and family issues, the West's multicultural character, and the tendency of westerners to view themselves as innocent victims when confronted with changes not to their liking.

Urling Coe was born in Kirksville, Missouri, on July 9, 1881. The son of a physician, Coe followed in his father's footsteps, attending college at the University of Missouri and receiving his medical training at Eclectic Medical College in Cincinnati, Ohio. In an era when attending a public high school was only starting to become common and college attendance was rare, Coe' education and profession as a licensed medical doctor set him apart from most of his contemporaries. But what he has to say is by no means unrepresentative of his time and place.

A number of his educational experiences typified larger trends in American society during the late nineteenth century. As an undergraduate, Coe, for example, played football and baseball, activities characteristic of the era's concern for athleticism, while his post-graduate work in psychology reflected the rising importance of science, professionalism, and the developing therapeutic culture in American life. Moreover, Coe's educational training rendered him an observant commentator on public life, while his role as a doctor made him privy to the personal lives of people from all walks of life.

Time and place also add to the importance of what Coe has to say. For Urling Coe's early life spanned an important transitional era in American life. Industrial America had come of age, with Oregon, too, moving from a settler to an industrial society in the I880s. But like any period of fundamental change, this time brought forth contradictory feelings of optimism and fear, hope and anxiety, and spawned a social, political, and economic reform movement labelled Progressivism.

No state was more affected by that reformist impulse than Oregon. Indeed, Oregon was one of nation's leading Progressive states. Politically, Oregon enacted an initiative and referendum law (1902) and the direct primary (1904), provided for the recall of elected officials (1908), legalized a presidential preference primary (1910), created a public utilities commission (1911), and adopted women's suffrage (1912). In addition, the state passed a number of social welfare measures between 1900 and 1912 that included a minimum-wage law for women, a ten-hour day for women who worked in factories and laundries, a child-labor law, a law that raised taxes on public utilities and public carriers, a compulsory school -attendance law for all children until fourteen years of age, the creation of a board of health, and the establishment of a state forestry commission. It was in the midst of this reform movement that Urling Coe came to Bend.

Like so many single young men who came before and after him, Coe travelled to a relatively unsettled western area for adventure and opportunity. The Bend to which Coe came in 1905 was a new settlement, but one bustling with optimism. The individual water diversion ditches characteristic of nineteenth-century irrigation were giving way to irrigation companies and water districts that could pool capital to create larger-scale water diversions by the end of the century. Bend and much of Central Oregon were the recipients of such irrigation works. Irrigation brought not only an increased volume of water to the land but an infusion of capital and people that seemingly insured the area's growth and prosperity. Eastside aridity no longer would inhibit growth. The limitations of the natural world could be surmounted through human engineering and technology.

Water was certainly an important factor in the decision of Coe and other turn-of-the-century settlers to cast their lot with this Deschutes River settlement, but it was not the only reason. There was also an expectant hope that the railroad would soon connect Bend to the outside world, via The Dalles. The fulfillment of that dream came in October 1911, and with it an even more cosmopolitan Bend.

Bend in 1911, then, was a different place from the town Urling Coe had come to in January of 1905. The month prior to Coe's arrival, Bend had taken a tentative step toward respectability by voting into office its first mayor, councilmen, and minor officials. Nonetheless, the town still very much evidenced an open character that Coe does not hide, noting the people living in tents, the large number of saloons, houses of prostitution, the absence of sewers, and the lack of a municipal water or lighting system. That vibrant, if not entirely orderly, picture contrasts sharply with the Bend of 1911.

As people disembarked from the train at Bend on the newly completed railroad, they found a prosperous, respectable community with a town band, a school, churches, automobiles, graded streets and sidewalks, health ordinances, licensed saloons, and codes to regulate town building. These were reflective of how Bend's residents felt about themselves and the image of a stable, civilized, and progressive people that the town wanted to project to others. Bend had truly become an important center of industry, commerce, and culture. The railroad not only linked Bend to other intra- and inter-regional metropolitan centers, but also tied local hinterlands to Bend.

The emergence of Bend as a town center is nicely told, but the heart of Coe's reminiscences is in its title, Frontier Doctor. The book gives a vivid account of what it was like to be a young physician in frontier Oregon. The long hours; travelling in a buckboard or on horseback to reach settlers and ranchers miles from town in all kinds of weather; infrequent bill payments; the state of medical knowledge and procedures, including the use of medicines like morphine--all these and more are presented in a lively style. When medical surgeries are discussed, for example, the reader feels drawn into the incidents being recounted. Particularly interesting are Coe's birthing descriptions. Although male physicians were, by the early twentieth century, involved in childbirth, Coe still shows how much childbearing remained a women's ritual, with the gathering of neighbor women. He also vividly relates epidemic outbreaks of typhoid fever that plagued the Bend area until the town created better housing and sanitary conditions. Even a cursory reading of these accounts will remind a modern reader how tenuous Iife was, and why settler letters and diaries are filled with discussions about health.

But not all of Coe's medical battles were waged against disease. One of the most difficult problems the young doctor faced was to overcome folk traditions that hampered medical understanding and advance and the introduction of new medicines and medical practices. And while Coe's attitudes towards sex, venereal disease, marriage, divorce, domestic violence, abortion, and euthanasia may not sound startling to a present-day audience, they were not widely embraced or discussed by his early twentieth-century contemporaries. Yet current readers may be surprised about the prevalence of such practices as abortion or the use of morphine and interested in Coe's forthright statements regarding the worth of general practitioners over specialists and his opposition to "socialized" medicine.

Interesting and informative, Frontier Doctor sparkles with insights beyond those we might anticipate from a doctor. Here are themes often identified with the American West as a place of new beginnings, of open opportunity; here is the hinterland West as a resource dependent colony to intra- and inter-regional metropolitan places of economic power. Even traditional westerners, not always identified with Oregon's past--cowboys, rustlers, and cattlemen and sheep herders at war over rangeland--are colorfully sprinkled throughout the pages. Coe, for example, recounts in entertaining fashion episodes of being led to some out-of-the-way place to attend a rustler suffering from gunshot wounds received while on the job.

Yet pathos, too, is part of these stories. Hardships of farm and ranch life are not glossed over. The reader meets men and women who undergo much pain, deprivation, and struggle to sustain themselves. Occasionally those struggles proved unsuccessful, as we poignantly learn in the story about the wife of one homesteader living 28 miles south of Bend. While her husband and son spent fall and winter trapping in the Paulina Mountains, she ran the farmstead. Sick, but concerned about the stock, she ventured out into a particularly bad blizzard. That exposure to the elements worsened her condition, and she soon succumbed.

As this incident indicates, Coe also treats an important aspect of western history that currently is receiving increased attention: the central role of women in the westering experience. Historians are now discarding the stereotypes--the madonna of the prairie, the good-hearted prostitutes in the "untamed" west ' the town civilizers-- and instead reporting on the lives of real women. Coe presents numerous examples of just such women. As the preceding story suggests, women often bore the heaviest burden of western settlement. For some, life was cut short by death. Others sought release from loneliness and life's burdens through suicide, while most endured to build communities.

Another prominent theme in the newer western history is the importance of the urban West. It is well to remember that the West since 1880 has been the most urbanized region in the country. Here, too, Coe provides insights, illustrating how and why the small settlement of Bend was able to develop into an important town. Physical location was certainly important, especially the presence of water for power, irrigation, and human consumption. But so, too, was the optimism of town boosters and their success in attracting people and capital. The latter was particularly important, but proved to be a double-edged sword because much of the investment capital came from outside the area. Capital opened the town to economic and population growth but meant that external markets and investors largely controlled the form of development. Bend was being colonized. No force was more important in this process or was a better symbol of colonization than the railroad.

The railroad could make or unmake a town site. In this case it insured Bend's prominence, linking it to the wider world in 1911, as an increased number of people, natural resources, processed goods, and investment capital travelled the rails. Most notable were the large Shevlin-Hixon and Brooks-Scanlon timber companies. Following a railroad that provided access to the pine forests of the eastside Cascades, the two mills began operations in 1916. As in too many other places throughout the West, the result was a resource-dependent community, a boom-and- bust economy, and a situation where a geography of capital created an unstable geography of place. For profits did not depend on any particular place, but on the extraction of resources; then the capital was invested in the next place which offered resources and profit. Thus the stage was set for the resource-extractive, boom-and-bust economy that has dominated the history of Oregon and the West.

A further theme among historians of the West is westerners' ambivalent relationship with the federal government. Americans generally, and westerners in particular, like to think of themselves as rugged individualists. Yet individuals and communities in the West have always relied on the federal government for services they could not provide for themselves. It was the federal government that sponsored exploratory mapping expeditions and provided the American public with detailed knowledge about the region. The national government secured land claims to the West by treaty and war, offered a legal and military shield of protection to settlers, gave lucrative land grants to private parties to construct transportation systems, and supplied bureaucratic agents to regulate and develop the area. Conversely, the West offered the central government the means to extend its power and influence through those agents and bureaucracies. In a very real way the West and the federal government grew up together.

Coe provides insights into that inter-dependency, but clearly federal land policy was one of the most significant items in that relationship. The unorganized public domain in the West provided the national government with a powerful instrument for shaping the area by either retaining federal ownership of the land or determining the time and basis for its disposition.

Most Americans know about the famous Homestead Act of 1862, but few are probably aware of the 1909 Homestead Act. This so-called Enlarged Homestead Act allowed a settler to claim up to 320 acres of unreserved public land that included no merchantable timber, was unfit for mining, and was nonirrigable. Although revised in 1912, the original act required five years residency on the land and that at least one-eighth of the acreage be cultivated within three years for ownership. Because most of the Oregon lands opened to entry under this act were located in the central desert area, a flood of settlers entered Central Oregon. Encouraged by federal largesse, publicity in state newspapers,and promotions by the railroad, and wedded to a longstanding American belief that technology could overcome natural limitations--in this case aridity through dryland farming--homesteaders came to the area seeking independence.

Others who came to Oregon sought to profit from federal land policies in other ways. Timber companies paid dummy entrymen to file settlement claims, and then deed the land to the timbermen. Some individuals filed land claims in anticipation of being able to sell their forest land to large timber companies. Indeed, Coe himself made a great deal of money in timber land sales.

Today, the land-use relationship between westerners and the national government is still being played out through mining laws, oil depletion allowances, Forest Service logging contracts, and federal grazing fees. The federal presence is nowhere so pervasive as in the West. The federal government owns no more than 12 percent of any state east of a line running from Montana to New Mexico, but no state west of that partition is less than 29 percent federally owned. The national government owns 48.9 percent of Oregon's land. The tension that federal ownership sometimes creates, as Coe shows, is nothing new.

The creation of national forest reserves around the turn of the century (including the Cascade Range Forest Reserve in (1893), and regulations regarding them (particularly grazing rights), has a rather contemporary ring. Westerners appreciated a national government that facilitated economic opportunities for them to exploit, but resented a federal presence that sought overtly to direct the social, economic, and environmental outcome of government policies. This is another important aspect of western history that Coe writes about that is today receiving increased treatment. The transformation of Bend and the surrounding countryside changed not only people but the land.

Land and its seemingly inexhaustible abundance stands at the heart of American history, intertwining Americans' material lives and cultural perceptions. An abundant natural world supplied Americans' basic material needs while providing the "resources" for national economic growth. Nature's abundance provided the American people with "natural monuments" that rivaled European cultural artifacts, framed a distinctly American character, and seemingly assured a belief that Americans were a chosen people and the United States an exceptionalist republic, providentially destined to recreate the world in its own image. Americans have clearly conceived of their country, in Perry Miller's apt words, as "Nature's Nation." Oregonians in particular have thought of themselves and their place in those terms. It is land and not the Puritan migration, the American Revolution, or the Civil War that stands at the center of Oregon's history, art, and literature.

Coe, too, feels the power of the land. His reminiscences are replete with observations about nature. Moreover, since those observances are made in a manner common to his time-writing about "beauty" as framed, orderly landscapes; mountains as "sublime"; and forests as "virgin"--they provide a medium for understanding Coe and his cultural world. But most intriguing is how the land comes to shape Urling Coe's sense of place.

Not that Coe's feelings about nature are without ambiguity. If one word stands at the heart of the relationship that Coe has with the land it is paradox. The beauty, spaciousness, and bounty of the land provided him with aesthetic pleasures and a sense of openness. But Coe, as well as others, also looked to the land for security and economic prosperity. That required the land to be transformed from a "wilderness" into a "garden." Altering the course of streams, bringing domestic plants and animals onto the land, hunting, fishing, cutting trees, and other extractive endeavors reordered the landscape. Indeed, those actions were generally regarded as having "improved" nature. Coe and his neighbors felt a sense of pride and accomplishment in those civilizing changes. Yet Coe also expresses regret over what was being lost as a consequence of the actions he celebrates. In capturing his ambiguous feelings, Coe highlights another important aspect of the prevailing Progressive movement and a characterization that has marked all other periods of fundamental cultural change in American history: a concern for conservation.

By the turn of the twentieth century Americans showed a growing desire for preservation, conservation, and to experience first-hand a disappearing West. just as in the social and political arena of Progressivism, Oregonians were also participants in this area of reform. The state passed its first general wildlife conservation act in 1873 and created a State Board of Fish Commissioners to enforce fish and game laws in 1887, though it was not until funding for a wildlife protector was enacted in 1893, however, that Oregon made any real attempt to conserve its game population. Additional state and federal wildlife protection laws came during the I890s. A watershed in Oregon wildlife conservation occurred with the establishment of a State Board of Fish and Game Commissioners and the appointment of conservationist William L. Finley as State Game Warden in 1911.

But conservation extended beyond game animal preservation to include a back-to-nature movement. This took a number of forms, including tourism and the creation of literary works like Jack London's The Call of the Wild and Edgar Rice Burrough's Tarzan of the Apes. It also led to nature excursions. Oregon organized the first mountaineering club in the West, the Oregon Alpine Club, in 1887. During the last decade of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, the Alpine Club, reorganized and renamed the Mazamas in 1894, became an active voice for conservation measures in Oregon. The last decade of the nineteenth and the first decade of the twentieth centuries witnessed the creation of national forest reserves in Oregon, the establishment of Crater Lake National Park (1902), Governor Oswald West's proclamation preserving the state's beaches for public use in 1911, forest fire suppression laws, and the establishment of urban parks.

Not that all Oregonians supported those measures. Indeed, Coe demonstrates that passage of laws is one thing, but enforcement something else. He writes about the enactment of fishing and hunting regulatory laws but also notes, as in other places, that the limited number of game wardens and local traditions continued to govern the taking of fish and game in the Bend area. Americans, after all, viewed the taking of wildlife as a right. Hunting limitations carried the aristocratic mantle of European exclusion, for in Europe hunting preserves were restricted to the upper class. Such class distinctions did not sit well with a people who saw themselves as democratic and egalitarian. Accustomed to viewing wildlife as a "commons" free for the taking, most settlers viewed restrictions and arguments that the state owned the commons as an infringement on individual rights. initially, therefore, few submitted to the law.

Coe's own reactions to conservation measures are mixed, particularly from a retrospective vantage point heavily tinged with a personal political agenda for state home rule. He admires the hardihood of the settlers, lumbermen, and stockraisers, but deplores the decimation of pronghorns, deforestation, and the destruction of the "wildness and primitive beauty of the land." If Coe's feelings about the freedom to exploit nature remain ambiguous, he never looks too closely at the dominant cultural belief system to see what role it played in the exploitation of both nature and humans. He does not criticize capitalism's ethos of cash-value exchange, selfinterest, competitive materialism, unlimited expansion, freedom as a function of possession, or nature as a mere capital resource to assist in the accumulation of wealth.

The problems created by exploitation have always seemed to be merely an unfortunate by-product of progress. At times, however, the consequences are too overwhelming to be dismissed as merely regrettable. When the Central Oregon homesteaders who took up claims on the semi-arid plains under the 1909 Homestead Act faced economic, social, and ecological disaster, in true western fashion Coe lays no blame at the door of railroad promoters or "innocent" homesteaders. Rather, he blames the federal agricultural "experts" in the General Land Office who told homesteaders the land was suitable for dry farming. Thus have westerners yesterday and today been able to sustain themselves on a "myth of innocence," blaming others for their problems.

The relating of important themes in western history, whether intentional or not, remains riveting because Coe does not let abstract processes overwhelm the story, which is full of colorful, first-hand stories about actual people. Further adding to the book's readability is Coe's wit, including a self-deprecating humor. Working extended hours during a typhoid outbreak, Coe returned to his office tired, dirty, his feet swollen and blistered:

I went to the drug store to get something I needed badly, but I could not remember what I wanted when I got there. I could force my body to move by sheer will power, but my brain refused to function--it was played out. It was natural, I suppose, for the weakest part of me to give out first.

Urling Coe moved in 1918 from Bend to Portland, where he continued to practice medicine as a general practitioner and cardiologist. Coe died on May 9, 1956, at seventy-five years of age. The people Urling Coe helped bring into the world and the patients he served were not the only ongoing legacy in which he could take pride. In Frontier Doctor he has left scholars and the general public a work that adds to an understanding of Oregon's past and present. Urling Coe provides readers with more than a glimpse into his world; he speaks to ours as well. Numerous policies Coe wrote about are still at issue today. One does not have to share all of the doctor's perspectives--his racial attitudes or his views on abortion-to genuinely benefit from reading this account.

"If you know today's city of Bend in Central Oregon, reading the newly issued Frontier Doctor by Urling C. Coe will be a trip to an exotic land."