With

Thanksgiving quickly approaching, it’s easy to get lost in the fervor of the

holiday season or the concerns that surround family gatherings. Author Penelope

S. Easton joins us today with a reminder of what the Thanksgiving celebration

is truly about. Below, she details an incident that occurred early on in her stint as a dietary consultant in Territorial Alaska. You can

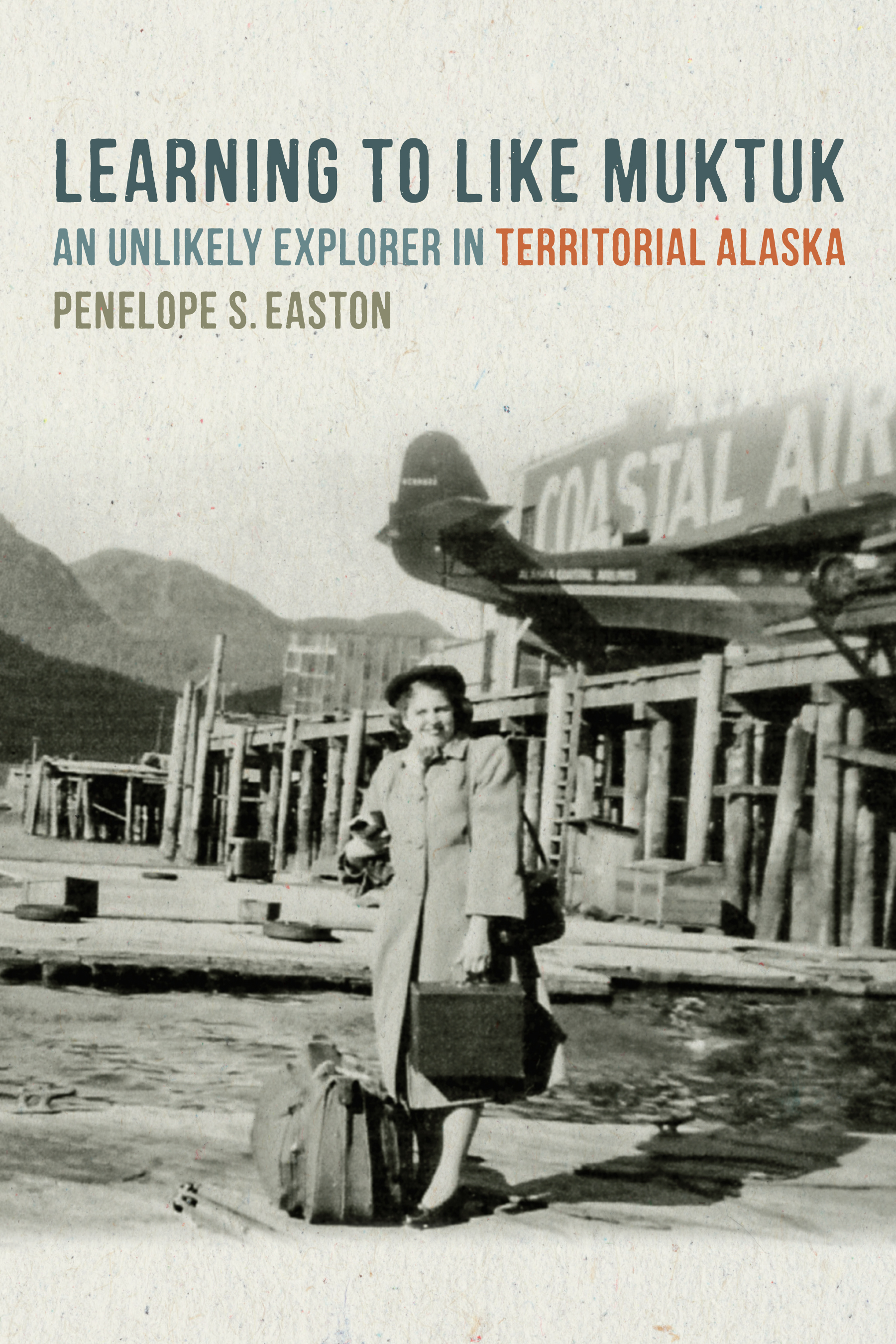

read more of Penelope’s adventures in her recently published book, Learning to Like Muktuk.

______________________

Thanksgiving at Kanakanak Hospital, 1948

My

first ride with a real bush pilot ended with landing on the snow-covered runway

in a gale-force wind at Dillingham, Alaska. Schoolboys and their fathers rushed

to save my luggage and the small amount of unloaded freight

from being blown away. They held down the Piper Cub and me until the chief

engineer from Kanakanak Hospital picked me up in a small truck for the six-mile

trip southwest on snow-covered, rutted roads. Thanksgiving was only five days

away, but it was the furthest thing from my mind at that moment.

When my arrival as the new dietary consultant for the Territorial Department of

Health had been announced in August of 1948, the Kanakanak people had requested

help with weevils in the flour and “smelly” eggs. Instead of facing what should

have been easy problems like those, I found a full- blown food shortage crisis.

I didn’t believe such gloom was well founded until Betty Riley and I finished

our inventory late that night.

Kanakanak Hospital was one of the bigger ANS

hospitals, serving the whole Bristol Bay area, and could be reached only by

boat or plane to Dillingham. One cook and two helpers prepared three meals a

day for fifty people: thirty Native patients, ten of whom were children, as

well as contract medical staff and local employees.

Food deliveries came by barge in the summer

months to all Alaska Native Hospitals in the northern areas. Desperately needed

food might not arrive for as long as ten months. When it did come, no one was

certain what the order would include because it had been submitted nearly two

years before by a chief nurse, untrained in food purchasing, and who had already left the Territory. Betty was new

and unfamiliar with such ordering, but she

was bright and cheerful and together we came up with ridiculous solutions, which lightened the tragic outcome of our night’s

work.

In November the storeroom should have had enough

canned goods to last more than 300 days. Instead we found nineteen cases of corn and spinach, and enough slippery peach halves

in thick syrup for one serving per person per day. No other fruit and

vegetables were left. There was less than a month’s supply of meat and fish. A

favorite protein source for the children, peanut butter, was rancid. Even more

disappointing was the 630-days’ supply of soon to-be-rancid butter.

There

had been no doctor at Kanakanak when Dr. John Libby had arrived earlier in the

year. Since the shortage of food supplies was creating low morale among the

staff and patients, he had already sent an emergency request for food to the

Alaska Native Service Director in Juneau. Dillingham was a rapidly changing community, shifting from one

where the people had lived from the land to one where they worked in canneries, so there was no local food available.

My

reception by hospital personnel was complicated because the staff thought I had

been sent to solve the food problem. I didn’t learn until my last day that they

didn’t realize I was on a routine visit and not Juneau’s answer to their

problems.

No plans had been made for any special

Thanksgiving dinner, and there seemed little reason for anyone to be thankful;

but I thought we should make some effort to celebrate. Betty and the cook were eager to join

me. The hot rolls that the cook made from some flour rescued by sifting out the

weevils helped improve the plate of canned beef and gravy, canned corn and

spinach. I had found some condensed milk in the nearly empty refrigerator. We

diluted and flavored the rich, sugary mixture and made some freezer ice cream

to have with the ever-available slippery peach halves. Although I was not

particularly crafty, I did know how to make some nut cups from yellow copy

paper. The cook filled them with brown sugar fudge from the almost solid brown

sugar. We used orange sheets from X-ray film packages for tray covers.

We received some favorable comments

but knew such cosmetic changes were not a solution to the food crisis. At a staff meeting the day before I left,

a nurse, realizing that I was an innocent

party to the sad conditions, said she was glad I didn’t blame them for eating

the favorite foods too quickly or make outlandish suggestions for future menus.

I didn’t know whether her fear of such behavior was due to the fact that I came

from Juneau or because I was a dietitian. Members of my profession were not

always perceived as being practical or understanding.

My

detailed, urgent report to ANS headquarters received no more attention than did

the doctor’s. Food supplies did not arrive for many months. Spring found some

of the contract nurses leaving for the lower forty-eight because they were

unwilling to suffer through such food-related hardships and became

disillusioned with the romance of Alaska.

But Betty and loyal staff stayed to make the best of the situation, form

plans for the next Thanksgiving, and enjoy the long awaited sun, fresh fish and

beautiful berries of seasons to come.

I spent several weeks teaching nutrition classes

for school children and women in the community.

The weather delayed my return to Anchorage three times. Finally, the boys and

men who had greeted me loaded my luggage for my departure and waved the bush

pilot, me, and the Piper Cub off.

______________________

Penelope S.

Penelope S.

Easton learned from an early age to “make do” with what she had, leading to a

vibrant spirit of adventure that was essential in preparing her for work in

Territorial Alaska. Over a long and distinguished career, she would serve as a

clinical dietitian, nutrition consultant, school food service supervisor,

professor of dietetics and research assistant. Born in Vermont during the Great

Depression, Penelope now lives in Durham, North Carolina. At the age of 91, Learning to Like Muktuk is her first

book.