ISBN 0870713876 (hardcover)

Pacific Northwest Women, 1815-1925

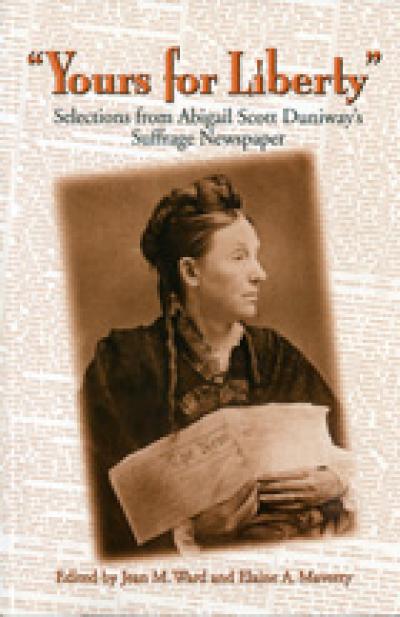

Jean M. Ward and Elaine A. Maveety

A new view of western history is emerging, one that recognizes the experiences and contributions of all peoples who lived in or came to the American West. Pacific Northwest Women, a remarkable collection of stories, essays, memoirs, letters, and poems, contributes to this new understanding and challenges many myths about women who lived and worked — and wrote — in the West.

This anthology gives voice and interpretation to the experiences of a diverse group of women, all of whom were part of the Pacific Northwest, defined here as Oregon and Washington. The editors, in addition to asking how race, class, and gender affected these women's experiences, examine what role place played in shaping their lives.

Selections by more than 30 authors illustrate the diversity of women's experiences in the Northwest between 1815 and 1925. Many of the pieces have been neglected or overlooked in studies of western women; some have never before been presented to contemporary audiences. The selections are arranged according to four recurring themes: connecting with nature, coping with circumstances, caregiving to others, and communicating for the self and others. Each author is introduced in an essay that includes biographical information and provides historical and cultural context for a contemporary reading. The essays also explore the modern-day concept of empowerment in the experiences of these women.

Includes selections by Nancy Perkins Wynecoop, Alice Day Pratt, Ella Rhoads Higginson, Anne Shannon Monroe, Narcissa Prentiss Whitman, Amanda Gardener Johnson, Margaret Jewett Bailey, Abigail Scott Duniway, Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins, Sui Sin Far, and Hazel Hall.

About the author

Jean M. Ward is professor of Communication and director of the Gender Studies program at Lewis & Clark College.

Read more about this author

Elaine A. Maveety has an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Oregon and is coordinator of Lewis & Clark's annual Gender Studies symposium.

Read more about this author

Introduction

Part I: Connecting With Nature

Nancy Perkins Wynecoop

"The Song of the Generous Supply and Able-One, My Grandmother"

"Able-One Was Afraid

Emily Inez Denny

"We Live Close to Dear Nature

Caroline C. Leighton

"A Fit Home for the Gods"

Frances Auretta Fuller Victor

"A Font of the Gods"

Alice Day Pratt

Nature Has Not Betrayed the Heart That Loved Her"

Ella (Rhoads) Higginson

"I Am a Mossback to My Very Finger Ends"

Part II: Coping: Learning By Doing

Anna Maria Pittman Lee

"If My Life is Spared"

Sarah J. Lemmon Walden Cummins

"My Will Was Not to Be Swayed"

Bethenia Owens-Adair

"I Felt Equal to Almost Any Task"

Esther M. Selover Lockhart

"It Was Up to Me"

Emeline L. Trimbel Fuller

"I Nerved Myself"

Mother Joseph of the Sacred Heart, S.P. (Esther Pariseau)

"How Fervent Was Our Te Deum"

Susanna M. Slover McFarland Price Ede

"We Parched Peas for Coffee"

Anne Shannon Monroe

"I Would Write, and Write, and Write"

Emma J. Ray

"I Became Disgusted with Portland"

Part III: Caregiving: Family and Community

Narcissa Prentiss Whitman

"This Orphan Family Under Our Care"

Elizabeth Sager Helm

""Stay Close to Me"

Tabitha Moffat Brown

"I Have Labored for Myself and the Rising Generation"

Amanda Gardener Johnson

"My First Duty Is to My Family"

Susie Sumner Revels Cayton

"Sallie the Egg-Woman"

Mourning Dove (Christine Quintasket)

"Helping the Needy"

Part IV: Communicating: From Private to Public

Margaret Jewett (Smith) Bailey

"What Have I Married?"

Mary P. Avery Sawtell

"Your Blows Have Divorced Us!"

Abigail Scott Duniway

"On the Road"

Minnie Myrtle Miller (Theresa Dyer)

"Miss Anthony's Lectures--Observanda"

"A Communication to the Public from Mrs. M.M. Miller

Sarah Winnemucca (Hopkins)

"They Take Sweet Care of One Another"

Sui Sin Far (Edith Maud Eaton)

"The Americanizing of Pus Tsu"

Ella (Rhoads) Higginson

"Eshter's 'Fourth'"

"Isaphene's White Hat"

Louise Gregg Stephens ("Katharine")

"I Am a Believer Now"

"Our Feathered Folk"

Lydia Taylor

"The Die Was Cast"

Hazel Hall

"Selected Poems"

Epilogue

Bibliography

Acknowledments

Index

Pacific Northwest Women gives both voice and interpretation to the cultural and cross-cultural experiences of a diverse group of women, all of whom were part of a particular geographic region — the Pacific Northwest, which we define as the area now known as the states of Oregon and Washington. In addition to asking how social constructions of race, class, and gender affected these women's experiences, we ask what role place — geographical region — played in shaping their lives.

Throughout the process of collecting, selecting, and interpreting Pacific northwest women's texts, we have been influenced by the thinking of western historians such as Glenda Riley, Peggy Pascoe, Patricia Nelson Limerick, and Susan Armitage. These historians remind readers of the virtual absence of women of all ethnicities in Frederick Jackson Turner's frontier thesis, as well as the stereotyping of American Indian women as drudges and Anglo women as Saints in Sunbonnets, Reluctant Pioneers, and Gentle Tamers in later "frontier" histories.

Limerick and others argue persuasively for a paradigm shift that moves beyond narrow, obsolete visions of "conquered frontiers" to a paradigm that includes all women and recognizes the diversity of women's experiences within and across cultures. In a discussion of prostitution in the early West, Limerick writes: "Exclude women from Western history, and unreality sets in. Restore them, and the Western drama gains a fully human cast of characters — males and females whose urges, needs, failings and conflicts we can recognize and even share" (The Legacy of Conquest 52).

Pascoe and Riley contribute to this new paradigm, and their ideas helped guide our development of Pacific Northwest Women. Pascoe addresses "the problem of disappearing women of color" and calls for multicultural western history that recognizes western women at the cultural crossroads — "an analytic crossing of three central axes of inequality — race, class and gender" ("Western Women at the Cultural Crossroads" 49). To enrich understanding of western women's experiences and to contribute to comparative regional studies of their lives, Riley urges adding region to critical considerations of gender, race, and class (A Place to Grow 12).

Pacific Northwest Women is a step toward regional recovery and interpretation of women's diverse voices, lives, and experiences.

Pacific Northwest Women

The lives and words of the thirty women who appear in this volume, along with the dozens of others we could not include, have sometimes amazed and frequently touched us during the course of this project. They still do, each time we reread them. Only five — Frances Fuller Victor, Betheniz Owens-Adair, Narcissa Prentiss Whitman, Abigail Scott Duniway, and Sarah Winnemucca — appear in Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary, 1650-1950, but all thirty are "notable" in the study of women's lives in the Pacific Northwest.

Who were these women? They were African American, Euro-American, Asian American, and American Indian. They were single, married, widowed, and divorced. They were missionaries, homesteaders, former slaves, nurses, schoolteachers, historians, architects, homemakers, doctors, migrant harvesters, milliners, newspaper editors, seamstresses, domestic servants, professional writers, poets, artists, suffragists, midwives, social workers, evangelists, and prostitutes. Some were born in the Pacific Northwest; some emigrated from other states or countries. Some were mothers; some were childless. Some were able bodied, others lived with physical impairment. Several survived oppression and even brutality, loss of families and loved ones. Some died young — in childbirth, from illness, or by violence. Others lived long, productive lives. A few just disappeared, and we do not know the end of their stories.

They were women of spirit, courageous and resourceful; they were ordinary and yet extraordinary, each in her own way. They told of living with nature, of coping with challenges, of caring for others, of communicating their messages. They were builders — of schools, hospitals, and orphanages; of homesteads and farms; of families and communities; of novels, stories, and poems. They were recorders and keepers of stories, makers of songs.

All of these women lived, at least for a number of years, in the Pacific Northwest, the vast geographical area now known as Oregon and Washington, twin states created and bonded by nature to share geology and climate, and therefore much of their history and culture. From the beginning, the region was culturally diverse; prior to the arrival of Anglos, a variety of Indian cultures thrived. After the arrival of fur traders — followed by missionaries, pioneers, miners, ranchers, and homesteaders — the landscape began to change. Fertile lands west of the Cascade Range became farmlands; drylands east of the Cascades became ranches and homesteads.

Although we use the term "culture" throughout this work, the women and men who came together in the early Pacific Northwest did not use this word to represent their systems of beliefs, customs, and behaviors, and they would not know the meaning of "standing at cultural crossroads." The concept of culture was a creation of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and was not a part of the thinking of those who came west in the nineteenth century. From a contemporary point of view, Euro-American visions of the world were typically ethnocentric, and their attitudes — linked to prevailing distinctions between "savagery" and "civilization" — were often racist. "Savagery," Patricia Limerick writes, "meant hunting and gathering, not agriculture; common ownership, not individual property owning; pagan superstition, not Christianity; spoken language, not literacy; emotion, not reason" (The Legacy of Conquest 190).

With the arrival of Euro-Americans in the Pacific Northwest, conditions for Indian women changed dramatically over time. Before the Anglos came, the Colville ancestors of Able-One and Mourning Dove lived in harmony with nature, relatively undisturbed at their hunting grounds in the upper regions of the Columbia River; the Northern Paiute ancestors of Sarah Winnemucca traveled in nomadic bands, hunting and gathering in seasonal rounds that took them to what is now Southeastern Oregon as well as into Nevada and California. But, as told in the narratives of these Indian women, arrival of Euro-Americans eventually pushed their people to the very edge of survival. Although Sara Winnemucca, Mourning Dove, and Nancy Perkins Wynecoop (the granddaughter of Able-One) assumed roles as mediators between Indian and white cultures, they could not restore the lost cultures of their grandmothers and their great-grandmothers.

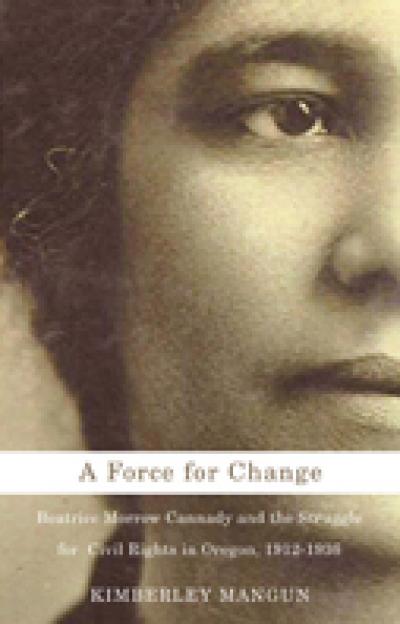

As settlement continued, African-American and Asian-American women came to the cultural crossroads of the Pacific Northwest. Women such as Emma J. Ray, Susie Revels Cayton, and Sui Sin Far acted as what we term "cultural mediators" and addressed issues of race, class, and gender in their writings and interracial community efforts. They, like the American Indian women whose narratives are included in this collection, were what historian Peggy Pascoe calls "intercultural brokers, mediators between two or more very different cultural groups" ("Western Women at the Cultural Crossroads" 55).

For Anglo women, including early missionaries, the Pacific Northwest was also an intersection of contrasting cultural values. Separated by great distance from centers of white culture and sometimes ill equipped to understand or accept the Indians as anything but "other" some women, such as Narcissa Prentiss Whitman, responded by retreating into private cultures of their own creation, literally closing the door to the "other." Emeline Fuller, traumatized by a childhood experience, did not make distinctions as an adult between and among Indians, and she classed all as one hostile group. In Emily Inez Denny's myopic vision, Indians were curious parts of the landscape — interesting figures in her own childhood playground.

For other white women, several of whom became cultural mediators, the Pacific Northwest was a place to learn about and appreciate Indian culture and language — to empathize with and respect indigenous peoples as individuals. This was the case for Mother Joseph of the Sacred Heart, S.P., in her work and travels throughout the Pacific Northwest, and for Susanna Ede, who became matron and interpreter for the Indian School at Quinault Reservation. For Caroline C. Leighton, who shared her understandings with eastern readers, American Indian cultures were not threatening but fascinating and sometimes beautiful — not "savage" or "other" but simply different.

Two Women's Texts

For this volume, we have chosen oral histories and writings that illustrate the diversity of women's experiences in the Pacific Northwest during the early period of 1815 and 1925. We have not, however, emphasized overland journals and diaries since these are readily available in collections such as Kenneth L. Holmes's Covered Wagon Women: Diaries and Letters from the Western Trails, 1840-1890. And, because of our interest in the effects of geographic region on women's lives, we have not included travel accounts by women who briefly visited but did not live in the Pacific Northwest. many of the pieces we include have been neglected or overlooked in studies of western women. Some have received limited exposure, and others have never been presented to contemporary audiences.

Our decision to include a few reminiscences in this collection should be clarified. Because some of the women are recalling events that occurred many years earlier, questions about source credibility and function of memory are appropriate. Although the ability to recall details of early events can be keen in later years, the passage of time can also dim the memory, or the narrator may choose to alter details of events. If the narrator's recollection of fact was in error, we set the reminiscence aside; however, if a narrator colored or altered what we saw as her reality, we asked why.

All of the reminiscences we include from women in their seventies and eighties appear to meet the tests of memory and veracity. Elizabeth Sager Helm and Amanda Gardener Johnson, for example, were both in the eighties when they were interviewed, but nothing in Helm's balanced account of life with Dr. Marcus and Narcissa Whitman or in Johnson's brief narrative of her life in and out of slavery suggests failed memory or alteration of fact. Susanna Ede was also in her eighties when she narrated her life story for her family, and the detail she provides about living conditions in the early Pacific Northwest suggests a sharp, rather than dimmed, memory. Esther Lockhart published some of her recollections as early as 1898 and later gave the full story of her life to her daughter. Sarah J. Cummins did not publish her Autobiography and Reminiscences until she was eighty-six, but she states that her book was "copied from my diary as written in years long gone by: (7).

Two texts do, however, raise some interesting questions about memory and veracity, and both were written by women in their forties — Emeline Fuller and Emily Inez Denny. Emeline Fuller was only forty-five when she published Left by the Indians: Story of My Life. Although Fuller's prejudice toward all Indians strongly colors her narrative, her account of the events of what has come to known as the "Utter massacre," including the involvement of white instigators, largely corresponds with what historian Donald H. Shannon (1993) has found.

While Fuller was struggling for survival in 1860, Emily Inez Denny was enjoying what she describes as a carefree childhood in Washington Territory. Denny was only Forty-six when she copyrighted her autobiography, yet her description of early years in the Pacific Northwest appears colored already by nostalgia for a lost time. Of all the texts in this collection, only Denny's may fit historian Julie Roy Jeffrey's caution about pioneer and early settler recollections: "Nostalgia for lost youth colored their recollections, and the pioneer period became a golden age marked by youthful simplicity, virtue, and happiness" (Frontier Women 202). Even the title of Denny's autobiography — Blazing the Way — suggests romanticization of her culture and of the period.

In contrast to Denny's romantic view of the West, the number of separations and divorces that appear in these pacific Northwest women's writings may surprise contemporary readers. But, as historian Glenda Riley points out, "a proclivity to divorce" existed on the plains and throughout the West, and census records indicate that "western women sought and received a higher proportion of divorces than women in other regions of the country" (A Place to Grow 201). Riley adds that the cause for this high rate of divorce in the West is unclear but might have been related to economic opportunities and western women's desire for independence.

To preserve the authenticity of the women's voices, all selections in Pacific Northwest Women are presented in their original form, with the exception of a few paragraphing changes and infrequent use of "sic." Titles for the texts have been drawn from the women's writings and narratives. Ellipses and bracketed information, unless otherwise noted, are our work as editors.

One of our objectives in Pacific Northwest Women is to give readers more than snapshots — brief glimpses — of these women. Since most are not well known to contemporary audiences, even in the Pacific Northwest, we introduce them with essays which provide biographical information, introduce the themes we found in the women's writings and narratives, and set their lives and words within historical, social, and cultural contexts. In a few cases, full biographical information has not been found, and we trust that others, intrigued by our beginnings, will continue the process of recovering the lives of "lost" women. to assist in this endeavor, we provide an extensive bibliography for those who wish to pursue the works of women of the early Pacific Northwest.

The Four Major Themes

In the process of reading scores of texts by Pacific Northwest women, we identified four major themes: connecting with nature, coping with circumstances, caregiving to others, and communicating for the self and others. Despite the diversity of backgrounds and life experiences of the women, these four themes emerged again and again in their writings and oral narratives. To illustrate these themes, we selected representative texts from thirty women.

Pacific Northwest Women is arranged in four parts, each of which corresponds to one of the themes, and we introduce each part with an essay that explores questions we asked about the theme. To show each theme across time, texts within the four sections are ordered by approximate dates of the events described, not necessarily by dates of writing or publication. (The one exception to this ordering is Ella Higginson's 1892 essay, "A Mossback to My Very Finger Ends," which concludes Part I.)

In Part I, Connecting With Nature, we focus on the importance of nature in the lives of these women — their relationships and connections with the natural world of the Pacific Northwest. Six texts are included in Part I, but the nature theme reappears in many other texts in this volume. To explore this theme, we asked two questions: What does nature in the Pacific Northwest represent to these women? What are the similarities and differences in their responses to nature?

From Able One's early experiences of walking in balance with nature, to Ella Higginson's passionate appeal for stewardship of the natural world, the six women in Part I speak of living in connection with nature. We found no calls for taming the land, for conquest and subjugation of nature's landscape; instead, these women see themselves as part of — in harmony with — the natural world of the Pacific Northwest.

In Part II, Coping Learning by Doing, we examine accounts of "making do" and doing what needs to be done, a theme we found frequently in texts by Pacific Northwest women. To illustrate the theme of coping, we include texts from nine women. In our exploration of this theme, we posed two questions: What forms does coping take in these women's lives, and how diverse are their experiences? What factors appear to be key in the coping process?

From the letters of Anna Maria Pittman Lee, which give insight into how she coped with early missionary life and a difficult pregnancy, to the writings of Emma J. Ray, which describe racial discrimination in the early part of the twentieth century, these nine women provide diverse accounts of coping. For some, coping with challenging circumstances is achieved in partnership with husbands and in connection with families; for others, coping involves breaking away from family and asserting autonomy.

In Part III, Caregiving: Family and Community, we focus on concern for the welfare of others, both within the domestic circle of family and within the expanded arena of community. Although accounts of caregiving are commonly associated with accounts of coping, the two themes can and do appear separately. To illustrate this recurring theme in the experiences of Pacific Northwest women, we include six texts, one of which is fictionalized. As we read the texts, we asked two questions: What are the examples and forms of caregiving in these women's lives and writings? How does one learn caregiving?

From Narcissa Whitman's concern for care of the children in her charge, to Mourning dove's recollections of acts of caring by her family and others, diverse acts of caregiving are highly valued by the women themselves. the models for caregiving, who are usually older women, are almost as diverse as the acts performed. throughout these texts, women frequently define themselves and others in terms of their capacity to give care, which includes the ability to create and sustain connections with others.

In Part IV, Communication: From Private to Public, we address our final theme: communicating for the self and others, wanting to be heard and understood by a public audience. Women throughout this volume were motivated to author autobiographies, to recover the lives and stories of family members, to research and write history, to publish in newspapers, to take to the lecture platform, and to write fiction and poetry.

To focus on this theme, we present a variety of genres from ten wombed, including two writers of fiction and one poet. To understand the place of communicating in these women's lives, we asked two questions: Why do these women want to be heard and understood publicly? What forms do they choose for their communication?

From Margaret Jewett Bailey, who wrote of her life as a former missionary and an abused wife, to Hazel Hall, who was confined to a wheelchair and wrote poetry acclaimed for its universal significance, the lives and texts of these ten women represent a wide range of communication purposes and forms. Some, particularly those who entertained their audiences and did not challenge cultural norms, found enthusiastic readers. Others, particularly the social reformers and cultural mediators, were constrained by prescriptions for gender, race and class; they were more controversial and less well received. Whether they shared the personal or challenged the public, all of their texts are woman centered. Some of their messages are reflective, even lyrical; some are argumentative. For some of these women, the objective was self-expression and self-empowerment; for others, the objective included empowerment of others.

Empowerment through Autonomy and Connection

Theoretically, Pacific Northwest Women reveals much about woman's empowerment — empowerment of self and of others. Empowerment involves the ongoing processes of self-discovery, self-determination, and self-expression. The empowered person has the capacity — the agency — to act on behalf of self and others, sometimes as an agent for change. To empower means to strengthen, to increase viability. Empowerment is reciprocal, for the act of empowering others does not diminish but strengthens the self. Unlike power, empowerment does not imply the exertion of control, legitimate or otherwise, over others.

Every woman in the volume writes or speaks from a position with the authority or capacity to act. These women reflect on and display their own empowerment, and they often encourage the empowerment of others. When Anne Shannon Monroe writes about her decision to leave the unpleasant confines of the schoolroom to become and author, she is reflecting on her own empowerment; when Sarah Winnemucca takes to the lecture platform and later writes her autobiography, she is displaying empowerment; when Lydia Taylor warns mothers and young girls of the evils of prostitution, she is seeking to empower them.

We came to our conclusions about the centrality of empowerment in Pacific Northwest women's experiences after identifying and exploring the four major themes of the volume, which suggested that both autonomy and connection with others were important in these women's lives, especially in the enactment of coping, caregiving, and communicating. this led us to careful examination of the women's lives and texts to determine the less evident, quiescent theme, which we have identified and interpreted as women's empowerment.

Both autonomy and connection — separation and affiliation — are embedded in the empowerment of these women. Their capacitates to act — to be agents for themselves and others — are acquired through what we call "autonomy-based empowerment" and "connection-based empowerment." Autonomy-based empowerment involves development of the self through individuated separation from others; connection-based empowerment involves development of the self through relational connections with others. Both forms of empowerment appear in the lives and texts of these Pacific Northwest women, sometimes through accounts of simultaneous separation and connection.

Our interpretations suggest that new questions should be posed about women's experiences in the american West and elsewhere. Rather than simply asking what happened to women's personal autonomy or what supportive networks they enjoyed, we should begin asking how women were empowered or disempowered through autonomy and connection — through processes of separation and affiliation.

Also, the concepts used in exploration of women's experiences need clarification. For example, we believe what historians such as Gerda Lerner have termed "autonomy" is more accurately identified as autonomy-based empowerment. "Autonomy," Lerner writes, "means women defining themselves and the values by which they will live." This involves "moving out from a world in which one is born to marginality" and "moving out from a world in which one is born to marginality" and "moving out into a world in which one acts and chooses, aware of a meaningful past and free to shape one's future" (The Majority Finds Its Past 161-62). Lerner's definition of women's autonomy implies autonomy-based empowerment but does not speak directly to women's connection-based empowerment.

In contrast, psychologist Jean Baker Miller emphasized the centrality of connection in women's experiences. She argues for a revamping of the concept of autonomy to include the self-direction and self-determination that women achieve through affiliation with others. "Women are quite validly seeking something more complete than ability to encompass relationships with others, simultaneous with the fullest development of oneself" (Toward a New Psychology of Women 95).

In addition to Miller, development psychologists such as Carol Gilligan, Mary Field Belenky, Blythe McVicker Clinchy, Nancy Rule Goldberger, and Jill Mattuck Tarule recognize the importance of what we term connection-based empowerment in women's lives. Gilligan notes that "women's sense of integrity seems to be entwined with an ethic of care, so that to see themselves a women is to see themselves in a relationship of connection" (In a Different Voice 171). And, Gilligan writes, attachment with others, "the ethic of responsibility," can become "a self-chosen anchor of personal integrity and strength." Like Gilligan, Belenky et al. recognize women's quest for self and voice, for "a core self that remains responsive to situation and context," including affiliations with others (Women's Ways of Knowing 138). And, they add, women often gather the "essential wisdom" that "they can strengthen themselves through and empowerment of others" (47).

To explore the construct of empowerment in the experiences of the thirty women in Pacific Northwest Women, we asked two questions: How are these women empowered? What are the examples of autonomy-based empowerment? of connection-based empowerment? In our introductions to the texts and experiences of these and other Pacific Northwest women, we include discussion of autonomy-based and connection-based empowerment in their lives. Our interpretation suggests, for instance, that Anna maria Pittman Lee was empowered by her autonomous decision to become a missionary and by close bonds with her husband; Tabitha Brown's establishment of an orphanage and school in Oregon was linked to her independent resourcefulness and to the support she received from friends in Oregon. The lives, memories, and writings of these and hundreds of other Pacific Northwest women are rich resources for exploring the significance of gender, race, class, and place in women's lives; for discovering the themes that were central to their experiences; and for testing the construct of autonomy-based and connection-based empowerment.

"The extraordinary lives of thirty ordinary women in the Northwest are depicted through the use of their stories, letters, memoirs, and poems; history at its most personal, and utterly fascinating."

"If you have any interest in understanding what life was like for the women of the 19th century West, you must have this book."

"… a fascinating anthology on Northwest women in the early pioneer era… and — typically for an Oregon State University Press book — an excellent design and wonderful photographs."