ISBN 9780870711046 (ebook)

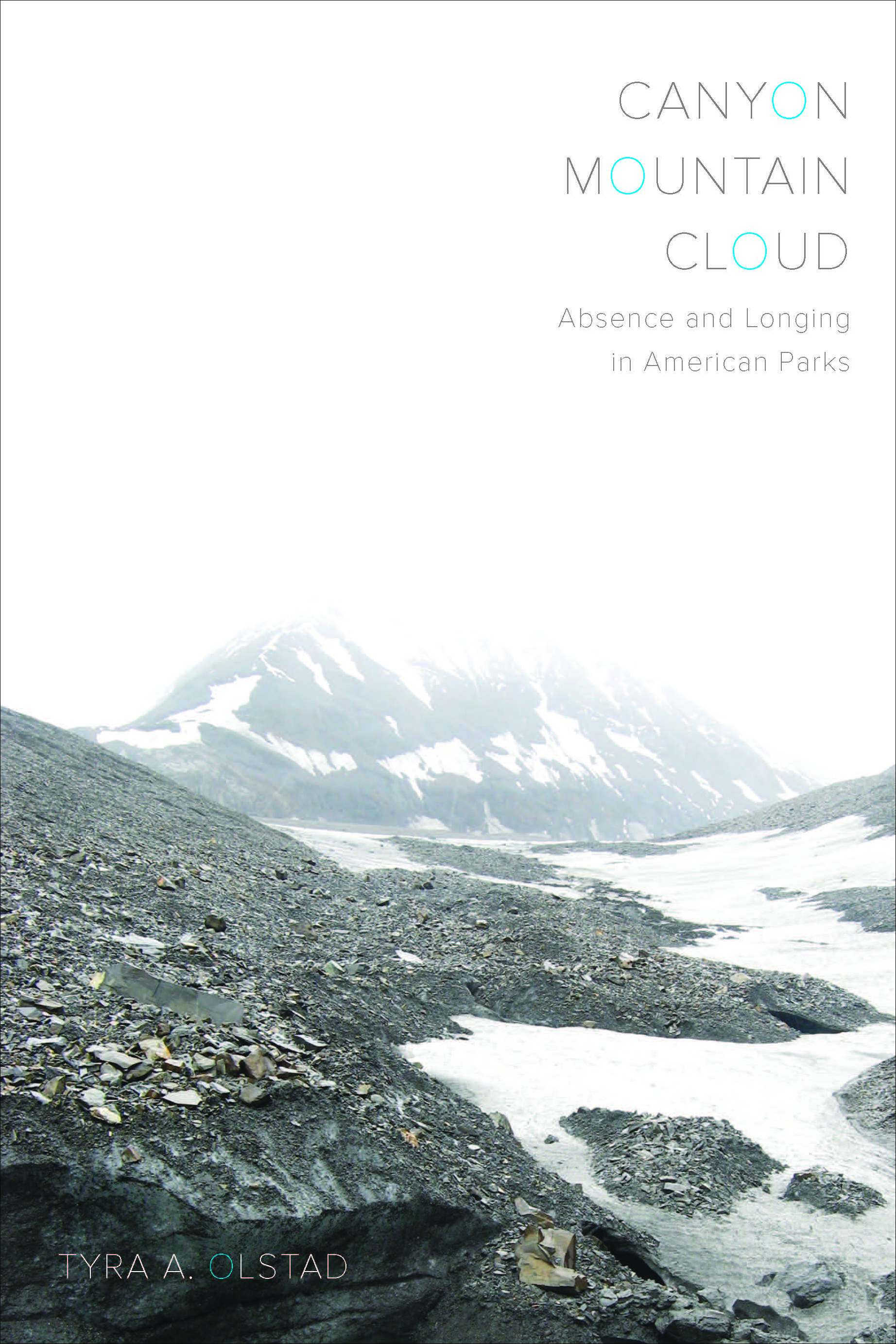

Canyon, Mountain, Cloud

Tyra A. Olstad

What do we seek and what do we find when we visit parks and protected areas? What does it mean to become so deeply attached to a beautiful, wild place that it becomes part of one’s identity? And why does it matter if a particular landscape doesn’t speak to one’s soul?

Part memoir and part scholarly analysis of the psychological and societal dimensions of place-creation, Canyon, Mountain, Cloud details the author’s experiences working and living in Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, Denali National Park and Preserve, Adirondack State Park, and arctic Alaska. Along the way, Olstad explores canyons, climbs mountains, watches clouds, rafts rivers, searches for fossils, and protects rare and fragile vegetation. She learns and shares local natural and cultural histories, questions perceptions of “wilderness,” deepens her appreciation for wildness, and reshapes her understanding of self and self-in-place.

Anyone who has ever felt appreciation for wild places and who wants to think more deeply about individual and societal relationships with American parks and protected areas will find humor, fear, provocation, wonder, awe, and, above all, inspiration in these pages.

About the author

Tyra A. Olstad is a writer, physical scientist, and former park ranger, paleontology technician, cave guide, summit steward, and professor of geography and environmental sustainability. In addition to one book—Zen of the Plains—she has published research articles, creative nonfiction essays, photo essays, and hand-drawn maps in a variety of scholarly and creative journals. She currently lives and works in southern Utah.

Read more about this author

Excerpt from Chapter 1

I am a plains person. I like my skies wide and my horizons distant. I like to see storms building and watch hawks soaring, smell sage baking and hear coyote singing, taste wind whirling and feel space, always space, more space, I need space, out on the plains.

Black Canyon is entirely un-plains-like. In addition to the verticality of the canyon itself, the park is hemmed in by ridges and, beyond them, the snow-capped peaks of the West Elk mountains to the east and the San Juans to the south. Worse yet, a century worth of fire suppression has allowed thickets of Gambel ("scrub") oak and serviceberry to proliferate. In places, it's nearly impossible to see much less move farther than a few feet through the brush. Neither prospect nor refuge, such tangles would discourage even the hardiest of woods-lovers. To a plains person, they're outlandish.

Waking early on the morning after my arrival, I stepped out of my apartment hoping to figure out where and what I'd gotten myself into. The air was fresh with the scent of newly fallen snow, the world quiet under an inch of white. Scrub oak crowded the edges of the staff parking lot, bleak tangled brown. A slight rustle; four deer materialized from the brush. They froze, considering whether I was cause for concern, then went back to browsing. I continued on to and along the main road, treading carefully on the ice-glazed pavement, listening for other signs of life. I'd intended to walk down to the first scenic overlook, but after a long, treacherous half-mile, still hadn't seen the canyon. Hadn't seen anything but the deer. Couldn't see anything. Just trees, branches, clawing at me, a claustrophobe. Where was the sky?

People don't go to Black Canyon to see the sky. They go to see a geologic wonder, a curiosity, a freak of nature unrivaled, according to the Park Service brochure, for its "narrow opening, sheer walls, and startling depths." They go to see the Chinese Dragons' silica-rich slithers and the Kneeling Camel's schisty lumps; maybe hike S.O.B. Draw down to the Gunnison River or rope in and climb up Chasm Wall. Those who study the park map may note a significant amount of acreage above the canyon rim- much of it designated "Wilderness"-but it's difficult to access and seemingly unremarkable (unless you too are a fossil nut who looks at the interbedded sandstones and mudstones of the Morrison Formation and dreams of dinosaurs.) No, the vast majority of visitors do what they do in every park-drive the road and pause at designated viewpoints; perhaps walk some of the trails, perhaps listen to a ranger talk; learn a few facts, foster a sense of appreciation; snap a few photographs, make a few memories; then leave.

I'd committed to a full field season, nearly five months. I was stuck. […]

I've been fortunate to have had opportunities to live and work at several parks and public lands: by then, Petrified Forest and Badlands National Parks, Fossil Butte National Monument, and Tongass National Forest. Moreover, I've visited a hundred-odd National Park Service (NPS) units (parks, monuments, preserves, historic sites, seashores, lakeshores, rivers, and recreation areas), not to mention several dozen Forest Service (USFS) forests and grasslands, Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) refuges, and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) conservation areas and checkerboard range. Wilderness areas, primitive areas; backcountry, frontcountry. State parks, county parks, city parks. Few forgettable, some memorable; most pretty, some beautiful. (What makes a place beautiful? What keeps it wild?)

Countless artists, philosophers, geographers, economists, ecologists, engineers, land managers, and people generally in pursuit of meaning and inspiration have asked these questions. They've come up with countless answers. […] Luna Leopold (son of the famous ecologist and writer Aldo) had made a "quantitative comparison of some aesthetic factors among rivers," with the ambitious goals to "eliminate personal subjectivity in landscape analysis" and to better inform land management (1969, 40). After developing a rubric for "uniqueness ratios for aesthetic factors" based on physical features (such as valley height vs. width, river pattern, and flow velocity), biologic and water quality (turbidity, algae, land flora), and human use and interest (accessibility, historic features, artificial control, pollution, and vistas) (1969, 2-3), he tested it by evaluating several sites in Idaho. He then compared top-ranked Hells Canyon to several national park landscapes, chosen based "on the assumption that national park status is a formal recognition of exceptional aesthetic quality" (1969, 10-11). While some of his premises are debatable-are braided channels objectively more beautiful than meanders? Why do cattails outrank water lilies? Is national park status a formal recognition of exceptional aesthetic quality?-his conclusion feels right: the Grand Canyon edges out Hells Canyon in both "Valley Character" and "River Character," and both exceed the aesthetics of valleys in Yellowstone. (At the visual resource conference, Gussow quoted mountaineer Willi Unsoeld: "'When I stand at the rim of the Grand Canyon, I ask: what is the value involved here to a human being? I'm not satisfied that it is just a pretty view'" [1979, 10]).

Had Leopold included Black Canyon in his analysis, it would have rivaled if not superseded Hells Canyon: steep gorge under distant mountains; powerful river; no sign of human impact (provided onlookers are unaware of three dams upstream). Spectacular view: from Tomichi Point-the first overlook-visitors gaze out into a nearly-2,000-foot deep abyss (shallow, compared with the 2,700-foot drop off Warner Point, at the end of the Rim Drive). Walls of dark, twisted rock jut skyward, a few foolhardy junipers and Douglas firs clinging to their edges. Distant but audible roar of water. Far below, the Gunnison River rages through the same channel it began cutting two million years ago, when it meandered through soft volcanic debris. (By the time it reached the hard Precambrian bedrock, it was so entrenched in its route that it had no choice but to keep cutting down.) Upstream, this section of canyon twists on a north-south axis. Early morning and late afternoon sunlight illuminates one wall and leaves the other in full shadow; promontory after promontory fades into the distance behind diagonal shafts of light. After a soaking rain or on warm mornings, the gorge belches mist. How to quantify those qualities?

Aside from Leopold, few scholars have tried to understand the unique aesthetic of canyons. Other landscapes have been thoroughly dissected, though. Mountains are often seen as sacred-avenues to the sky and links to the gods; "mountain as center, heaven, source, of water, place of the dead, and so forth" (Bernbaum 1990, 208). Pastures signify the Arcadian ideal and/or idyll. Cities represent human ingenuity and industry. Even factories and highways are celebrated as the vernacular-manifestations of social and cultural development and emblems of everyday life. Researchers evaluate people's responses to forests and fields, seashores and waterfalls, slums and Superfund sites, but canyons are overlooked (pun intended) as uncommon and aberrant.

An important distinction: aesthetically and geomorphologically, canyons are different from valleys. Carved by rivers or glaciers, broad V- or U- shaped valleys open to the sky and act as part of rolling landscapes-pleasant undulations that add variation to the view. Verticalwalled chasms that cut down instead of out seem inverted, unexpected, and unbalanced. When water incises too quickly to give other erosional forces time to catch up, it cuts an almost indecent peek into a planet we prefer to think of as solid. Like caves or caverns, canyons are remarkable for what they're not-for an absence of rock. The word "canyon" itself comes from a Spanish word for "tube"-something hollow, empty. "Chasm" from Greek for "yawning hollow, gulf"-disruptive, impenetrable.

The deeper a canyon, the greater the absence. It fills with winds, flowing erratically between pockets of air pressure. It distorts sounds, muffling some noises and amplifying others. Above all, it swallows light. "Gorge": from French "to swallow." Gorge, chasm, canyon: soulsucking emptiness.

Living on the thin skin of this earth, we rarely have reason to think of what's underneath our feet-the soil horizons, the bedrock, the continental crust that is to the planet the thickness of a shell to an egg. Canyons enable us to look down into the lithosphere and back through layers of time. Fascinating, to some; frightening, to others. If mountains are the abodes of gods, then canyons must be the realm of the devil. (Is "Hells Canyon" redundant?) Deep, dark, otherworldly places where the light doesn't shine.

Places in which one can become trapped. Places to avoid, to curse. Certainly not places to celebrate. […]

River, canyon, space: I certainly didn't know what to make of Black Canyon; didn't even know where to begin. Especially when compared with the open, spare lines of plains horizons, there's too much to see, think, and believe. What was I supposed to make of all of the distractions?: the color of shadow in the depths, the play of light along the rim. Distant roar of rapids. Warmth of rising thermals; coolness of swirling mist. Human history, natural ecosystems, the paleontological legacy that had brought me there. How was I supposed to fit into that landscape? Wild places-who do we become?