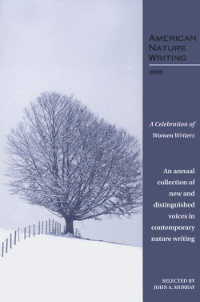

American Nature Writing 2000

John A. Murray

This acclaimed series, the leading showcase for contemporary nature writing, marks the new century and the new millennium with a special volume devoted to the writings of women. The 16 contributors to the book include 3 generations of women writers, both new and distinguished voices. The selections gathered here show American nature writing to be a vital and diverse genre, one that encompasses a range of themes: from the solace of wild places to the ferocity of nature, from the importance of urban green spaces to the need to protect the last of our wilderness areas.

In the words of the editor, John Murray, today's most gifted women nature writers "demonstrate the ability of women to move and change the world through the force of their words and the clarity of their vision." A wide variety of settings inspires the exceptional group of writers chosen for American Nature Writing 2000:

- a deer hunting contest in rural Georgia;

- a unique friendship forged between a group of women on a canoe trip through the White Mountains of New Hampshire

- a walk through the coastal rain forests of southern Alaska, 10 years after the Exxon Valdez oil spill

- a drive through suburban Maryland in search of crow roosting sites

- a white water descent of Chile's legendary Bio-Bio River

- a harrowing hike in the depths of the Grand Canyon

- a wilderness ranger's backcountry experiences with grizzly bears in the Teton National Forest

About the author

John A. Murray is the founding editor of American Nature Writing and the author of many books, including The Sierra Club Nature Writing Handbook. He lives in Denver, Colorado.

Read more about this author

Preface

Introduction

Trudy Dittmar, Moose

Jan DeBlieu, Mapping the Sacred Places

Cynthia Huntington, Tempest and Staying In

Emma Brown, High Country

Susan Zwinger, Coming of Age in the Grand Canyon

Alianor True, Chorus

Adrienne Ross, The Queen and I

Janisse Ray, The Faith of Deer

Geneen Marie Haugen, The Illusionary Distance Between Pacifist and Warrior

Pattiann Rogers, Surprised by the Sacred

Lisa Couturier, A Banishment of Crows

Kristen Vose Michaelides, Moving Water

Susan Marsh, Grizzley Bear

Carol Ann Bassett, White Water, Dark Future

Ellen Meloy, A Map for Hummingbirds

Kate Boyes, Out in the Desert: Four Views of a Western Town

Penny Harter, Selected Poems

Marybeth Holleman, In the Name of Restoration

Kathryn Wilder, The Grace of Geese

John A. Murray, Witness

Notes on Contributors

Permissions

i

"I have seen the extreme vanity of this world."

—Mary Rowlandson,

A Narrative of the Captivity of Mary Rowlandson (1676)

The story is told in our family of Celinda Fuller White, my great-great-great grandmother. After an ordinary and uneventful childhood on the Midwestern frontier, Celinda was abducted by Indians one day while picking berries. She was fourteen years old. For the next four years she lived among the Shawnee, finally escaping at the age of eighteen. For the rest of her life she remained close to the tribe, for she had been married to the son of a chief, and her log-cabin home became one of their last meeting places. In a corner of the basement in my father's home there is a heavy wooden box filled with artifacts — peace pipes, stone axe heads, projectile points, bear claws, a fox skin — that have come down to us from that distant time. I have often thought what a story she could tell. A brief biographical sketch of her life survives only because her son, Charles White Evers, my great-great grandfather, wrote an eight hundred-page local history (published in a ten pound leather-bound edition by J.H. Beers & Company of Chicago).

Of his mother he wrote:

"In her flight she came to a river beyond which she saw some men, at work, to whom she called, at the same time leaping into the water. She was none too soon, for her pursuers were on the bank before she could swim to the far side, which she did with great difficulty, in her exhausted condition. The men's rifles shielded her from further danger and she was restored to her surviving kindred. With all the hardships she endured in common with the Indians while in captivity, they treated her kindly and she always had a sympathetic word for them. Our house was a great resort for them, because she fed them, and could talk with them, both in word and sign language."

Some of the earliest writings by women about nature in North America are captivity narratives, most notably the account written by Mary Rowlandson, who was abducted during the Wampanoag uprising of 1676 in colonial Massachusetts. When I reflect upon the last three hundred years of nature writing by women in America I think first of this single body of writing, for it is in these simple but powerful journals that we first see European-American women separated from their native culture and put in close and continual proximity with wild nature. These first-person chronicles form the experiential and literary foundation for the immense body of nature writing by women that has followed. From these hardy pioneers and their personal records of capture and liberation, of courage and compassion, have come the many women authors who now loom large in our national literature.

One thinks first of such figures as the essayist Margaret Fuller, who was so admired by Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, and the poet Emily Dickinson, for whom nature was a central theme. By the late nineteenth century women writers such as Harriet Beecher Stowe (Palmetto Leaves) and Isabella Byrd (A Lady's Life in the Rocky Mountains) had begun to write popular nonfiction books about nature (central Florida and northern Colorado, respectively). Their works moved the process of literary empowerment one step further — from factually based adventure narratives to unified personal essay collections. At the turn of the century writers such as Ella Higginson (Alaska, The Great Country), Mary Kingsley (Travels in West Africa, and Mary Austin (The Land of Little Rain) continued to advance the cause of women in this regard, as all three became nationally recognized as professional writers. Overseas, the historic process was at work, as well, in the celebrated African writings of Beryl Markham (West with the Night) and Isak Dinesen (Out of Africa) during the 1930s and 1940s.

The life and career of Rachel Carson (1907-1964) represents both the culmination of a long struggle for opportunity and achievement and the beginning of a new period of increasing involvement for women writing about nature. The title of Carson's graduate thesis — "The Development of the Pronephros During the Embryonic and Early Larval Life of the Catfish" — gave little hint of the stellar works of literature that were to come. Later, in best-selling books such as The Edge of the Sea and The Sea Around Us, Professor Carson (for she taught marine biology at both the Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland) proved herself every bit the equal, if not the better, of any man (Edwin Way Teale, Aldo Leopold, Joseph Wood Krutch) then writing about nature. Her masterpiece Silent Spring, which detailed the deadly genetic effects of DDT, inspired President Kennedy to form a commission that led to the banning of the pesticide in the United States. Carson remains the standard against which the careers of all other women nature writers are judged.

Since then, many gifted women writers have followed in Carson's footsteps. One thinks of Annie Dillard, whose nature book Pilgrim at Tinker Creek was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction in 1975. Now a professor of English at Wesleyan College in Middletown, Connecticut, Dillard is especially committed to fostering the work of younger women writers. Another noted natural history writer who came of age in the seventies was Dian Fossey, an associate of anthropologist Louis Leakey (best known for his work among the hominid fossils of Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania). Her work Gorillas in the Mist focused on the plight of the upland gorilla in the volcano mountains of Rwanda. Following Fossey's tragic death, a major studio film was made by Universal Pictures about her ground-breaking work in Africa, with actress Sigourney Weaver in the role of the naturalist. More recently, in the 1980's and 1990's, acclaimed works by such writers as Terry Tempest Williams (Refuge), Linda Hasselstrom (Land Circle), and Gretel Ehrlich (The Solace of Open Spaces) have continued to demonstrate the ability of women to move and change the world through the force of their words and the clarity of their vision.

ii

What struck me the most as an editor in compiling this unique collection was the rich diversity of the writings, whether in terms of geographic location, theme, style or authorship. Three generations of contemporary women nature writers are represented here. The youngest writer was twenty when she wrote her essay (Emma Brown). The oldest writer is fifty-nine (Pattiann Rogers). Most of the contributors fall somewhere between these outer boundaries — of the elder practioner and the emerging author — and are established, middle-age members of the guild, with at least one book or significant periodical publications. Geographically, the selections range across the continent, from rural Georgia (Janisse Ray) to wild Alaska (Marybeth Holleman), from the rolling countryside near the nation's capitol (Lisa Couturier) to the rugged western mountains (Trudy Dittmar), from the Louisianna backcountry (Alianor True) to the deserts of southern Utah (Kate Boyes). Some writers speak of the gentleness of nature (Adrienne Ross) and others bear witness to its mercilessness (Susan Marsh). The selections also vary considerably in length, ranging from essays that can be read and appreciated in a few minutes to those that require the better part of an hour to read and ponder. Taken together, they provide a continent-wide view of a literary landscape every bit as diverse as the geographic territory that is America.

Although a common myth with respect to the eastern United States is that the region has been extensively humanized over the centuries and is lacking in wild areas, the women writers in this volume demonstrate that the east offers natural wonders every bit as lovely and striking as the west. Two pay tribute to the eastern sea coasts. For Jan DeBlieu, the mid-Atlantic beach is quite literally her home, as she, her husband, and young son maintain permanent residence on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. The dunes and lagoons, oak woods and salt marshes are her natural habitat: "Every day I set aside time to explore unfamiliar terrain and wonder at the great schools of fish, the falcons and sea birds that [migrate] past the islands with the tug of seasonal currents." Further north, Dartmouth English professor Cynthia Huntington writes of her summer cottage on Henry Beston's Cape Cod. The coastal sanctuary is a place of peace and calm, storms and tempests, sea gulls and blackbirds, a "landscape of memory" with unusual power to uplift the spirit and enrich the journey of life. Elsewhere in the east, Janisse Ray and Alianor True write of the naturalist's life in the Old South, of wild deer and leopard frogs and forests where honeysuckle fills the air with sweet fragrance. For Lisa Couturier and Julie Dunlap, as for the majority of Americans, nature is synonymous with the parks and forests of urban and suburban areas. Both women, who live in the greater Washington area, have found that nature is a powerful sustaining force, regardless of her size or scope.

The women writers of the west inhabit a landscape defined mostly by its open spaces — large expanses of public domain in which the human spirit finds a natural residence. The nature writers of the region are shaped by this abundance of wildness in a variety of ways. Susan Marsh is intimately familiar with the Yellowstone region and relates some of her backcountry experiences with grizzly bears. As a Forest Service ranger in the Tetons, she has seen the aftermath of grizzly attacks, and knows all too well the ferocity of the species. Similarly, her Wyoming neighbor Trudy Dittmar, living in a remote cabin, is often face to face with the local moose, a species every bit as dangerous as bears in certain situations: "Moose don't threaten, but neither do they make haste to yield." Geneen Marie Haugen, like Janisse Ray, looks at the effects of hunting on the land and on herself. Her essay probes the ambiguous and often contradictory depths of the subject. Further south Susan Zwinger describes a harrowing hike in the depths of the Grand Canyon, a trip on which she learns as much about herself, and about conquering the landscape of fear, as she does about the great barranca and its layered geology. Finally, Alaskan writer Marybeth Holleman offers an extended meditation on the complex, interdependent relationship of human culture and nature in the wake of the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster, a shipping accident in which a grounded supertanker disgorged eleven million gallons of crude oil into the pristine ocean waters of southern Alaska. In its lingering aftermath, she asks for "small acts" of "attentive love" that can, over time, "grow into long deep ocean swells" of positive change for nature.

Regardless of whether the writers are inspired by the countryside of the east or the old frontier of the west they are equally committed to nature, and to using language in its behalf. They know that words have power and books can change the word, if only one reader at a time. Their writings collectively attest to the fact that the genre is alive and well, even as the new century and the new millennium, those rarest of historical twins, emerge from the birth-canal.

iii

It is an axiom of intellectual history that political and social forces drive all great periods of artistic creation. This was as true during the Golden Age of Greece as it was during the Italian Renaissance or the French Revolution. We now find ourselves in a similar period, as all around the globe people restlessly seek a future in which culture and nature are more fairly balanced, and the ancient dream of universal human freedom is more fully realized. One has the sense, in the writings gathered here, that nature writing is poised at the beginning of a period of wonderful exuberance. All of the excitement that attends the beginning of a new century, and the start of a new millennium, is actively stimulating this historic genre. I believe that as nature writing attracts more and more gifted young talents, and addresses increasingly the political and social issues of our time, it will gain in stature and maturity, offering what Barry Lopez has called "a literature of hope." Nature teaches humility, generosity and balance, and nature writers share these values with a world often lost in hubris, greed and disorder. The best works of nature writing are yet to come, and they will most certainly be concerned with these and other eternal verities.