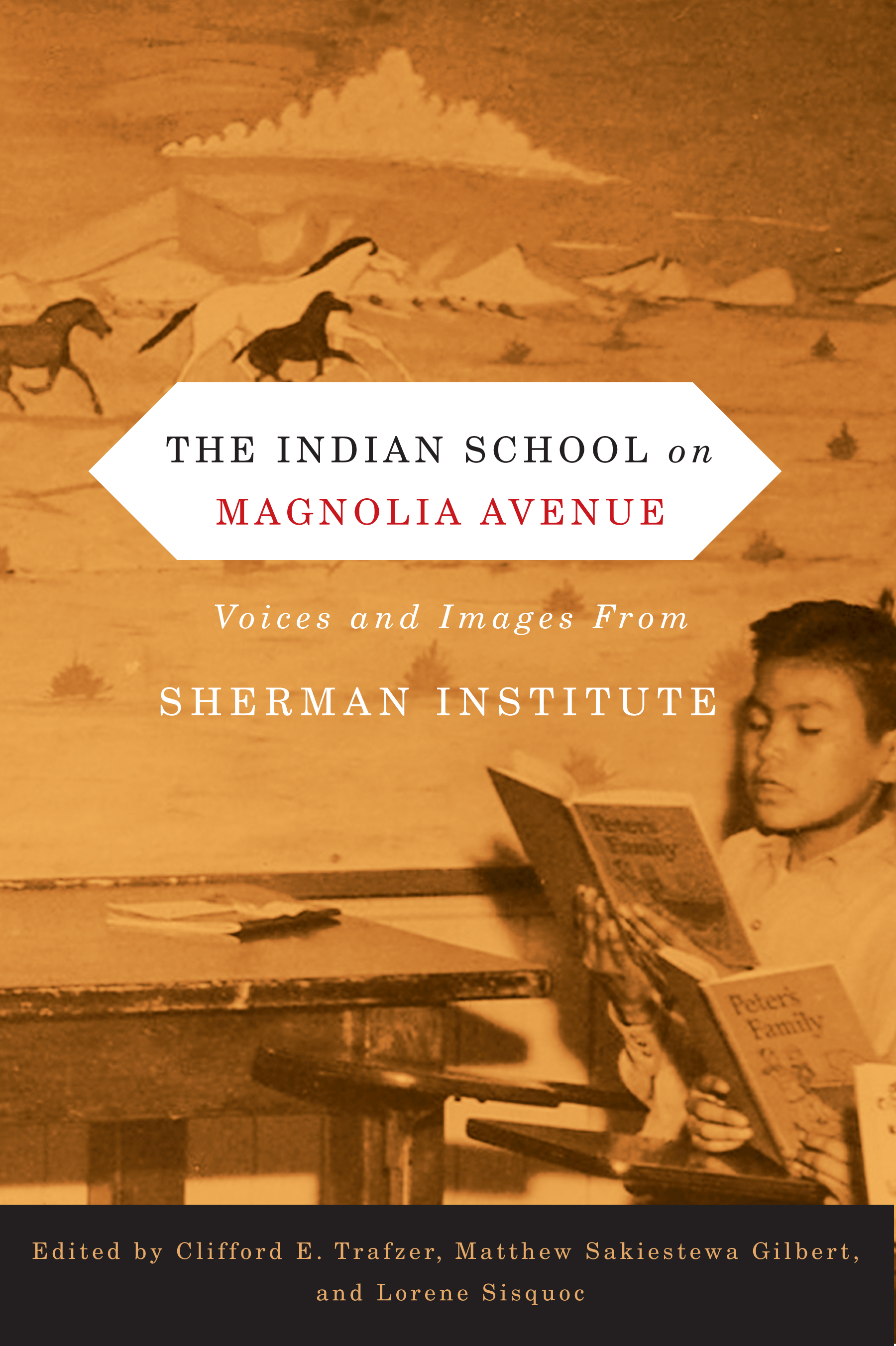

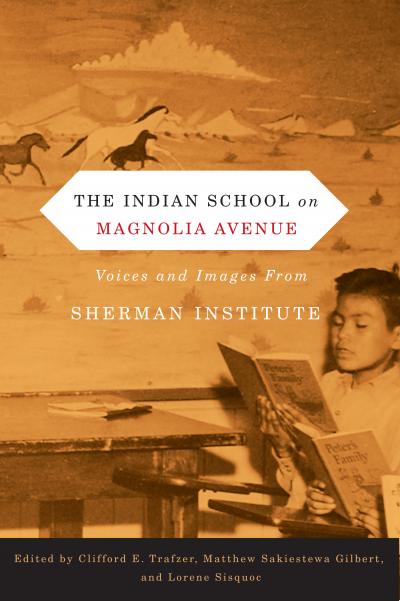

In 1902, the federal government opened the Sherman Institute in Riverside, California, to transform American Indian students into productive farmers, carpenters, homemakers, nurses, cooks, and seamstresses. The Indian School on Magnolia Avenue: Voices and Images from Sherman Institute, edited by Clifford E. Trafzer, Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert, and Lorene Sisquoc, tells the story of this flagship institution and features the voices of those who attended the school. The book is the first collection of writings and images focused on an off-reservation Indian boarding school. Contributors to the volume draw upon documents held at the Sherman Indian Museum to explore topics such as the building of Sherman, the school's Mission architecture, the nursing program, the Special Five-Year Navajo Program, the Sherman cemetery, and a photo essay depicting life at the school. In the following excerpt from the conclusion, Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert discusses his time spent conducting research in th e Museum's archival vault and his experience bringing his findings back to Hopi alumni of the Sherman Institute.

e Museum's archival vault and his experience bringing his findings back to Hopi alumni of the Sherman Institute.

[This excerpt is cross-posted at First Peoples New Directions.]

An Open Vault

by Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert

On a warm October day in 2004, I drove my car south on Magnolia Avenue in Riverside and made my way to Sherman Indian High School for the Sherman Indian Museum Open House. The event was a festive occasion, as alumni from across the nation came together to remember their school days and visit with old friends. Outside the Museum, the school’s choir was singing their alma mater, “The Purple and Gold,” and a group of older Sherman alums were taking refuge from the heat by sitting in the shade of a large palm tree. Near the school’s flagpole, children were laughing and playing, while their parents listened contentedly to the choir. The smell of frybread permeated the air.

When I walked inside the Museum, I saw people looking at old black and white photographs that hung on the walls. Another group of former students were flipping through the school’s large collection of yearbooks as they searched for themselves, friends, or relatives. Others stood peering into a glass cabinet, attempting to read the names etched on the school’s collection of trophy cups and medals. And in a side room at the east end of the Museum, Jean Keller was talking about her new book on student health at Sherman Institute. She was sharing at length about her work at the Museum and the documents she had uncovered in the vault. Jean says more about this in her book Empty Beds:

"The documents at the Sherman Indian Museum remain as they were when placed in the vault as long ago as 1902. Tissue pages of letterpress books remain stuck together by ink not completely dried when closed; loose documents are packaged in brown paper and tied with red ribbon. Lori Sisquoc (Fort Sill Apache/Cahuilla), curator of the Sherman Institute Museum, and I opened these records with care and wonder, cognizant of the incredible fact that we were the first to peruse these records of history since they were created lifetimes ago." [1]

I still remember the first time I stepped inside the Museum vault. I was a new graduate student at the University of California, Riverside, and I had come to the Museum to research Hopis who attended the school. Inside the vault, Lori Sisquoc, Director of the Museum, showed me documents of all kinds, including the administrative letterpress books that Keller consulted for her book. Lori told me that school officials such as Harwood Hall and Frank Conser used the books to make copies of their letters. Hall and Conser addressed the letters to students, their parents, high-ranking U.S. government officials, and superintendents of other off-reservation Indian boarding schools. Apart from the documents, items in the vault included photographs, pottery, and beautiful paintings.

During my graduate program, I returned to the vault on many occasions. When I was an intern at the Museum, I made a digital catalog of the vault’s one hundred trophy cups. While the school’s football and track teams had won several of these trophies, others belonged to individual students. Since my research centered on Hopis, I was on the alert for items in the Museum’s vault that related to the Hopi people. It did not take long for me to come across and catalogue trophies that Hopi students had won. Hopi runner Philip Zeyouma from the village of Mishongovi on Second Mesa won two first-place trophy cups in the collection. Zeyouma is known for winning the Los Angeles Times Modified Marathon in April 1912. His victory earned him an opportunity to run in the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden, but instead of competing, he returned home to his village community on the reservation.[2]

During my graduate program, I returned to the vault on many occasions. When I was an intern at the Museum, I made a digital catalog of the vault’s one hundred trophy cups. While the school’s football and track teams had won several of these trophies, others belonged to individual students. Since my research centered on Hopis, I was on the alert for items in the Museum’s vault that related to the Hopi people. It did not take long for me to come across and catalogue trophies that Hopi students had won. Hopi runner Philip Zeyouma from the village of Mishongovi on Second Mesa won two first-place trophy cups in the collection. Zeyouma is known for winning the Los Angeles Times Modified Marathon in April 1912. His victory earned him an opportunity to run in the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden, but instead of competing, he returned home to his village community on the reservation.[2]

The school and the Museum’s collections have special meaning for Native people. While the U.S. government created Sherman to weaken American Indian cultures and assimilate indigenous people into mainstream American society, Native students learned to navigate through federal Indian policies, and many of the students took advantage of their time at the school. My grandfather, Victor Sakiestewa, Sr. from Orayvi and Upper Moencopi, along with his brothers and sisters, were among the first group of Hopi students to attend Sherman in the early 1900s. By examining documents in the vault, I learned that my grandfather received high marks in the school’s Laundry Department,[3] and his sister, Blanche, worked as a housekeeper in the girls dormitory, the Minnehaha Home.[4] This information may seem insignificant to some scholars, but it provides my family with a glimpse of the early experiences of my grandfather and his sister at the Indian school in Riverside.

Providing Hopis with documents that I uncovered in the Museum’s vault was an important part of my research.[5] Not long after I started graduate school, I received permission from the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office to conduct interviews on the Hopi Reservation with former Hopi students. One of the people I interviewed was Samuel Shingoitewa, from the village of Upper Moencopi, who went to Sherman in the 1920s. Since many Hopis of his generation have fond memories of the orange groves that once surrounded the school, I brought him two bags of oranges from Riverside.[6] He was tired and hard of hearing when I interviewed him, but his mind was sharp. He told me about the military structure of the school and how he had earned the rank of “Expert Harness Maker,” an accomplishment that still evoked pride in his voice.[7] As our time together came to a close, I handed him a folder of short articles that he had published in The Sherman Bulletin, the school’s official student-written newspaper.[8] One was about the need for his peers at Sherman to take good care of their shoes, while a second focused on his involvement in the school’s harness shop.

Later in the afternoon I traveled east to the village of Bacavi on Third Mesa to interview Bessie Humetewa (Talasitewa) who went to Sherman from 1920 to 1928. During our interview, Bessie mentioned that she had stayed at Sherman “all eight years without coming home.” She recalled how her mother wept when government officials loaded her and a group of other Hopis on a wagon for Winslow, Arizona. Still feeling the pain of that moment, Bessie said that once they arrived in Winslow, they boarded a Santa Fe train for Southern California. As she recalled these details, she reminded me that Hopi mothers rarely showed this level of emotion in public.[9] While her departure to Sherman Institute was traumatic, Bessie learned to adapt and excel at the school. She made new friends, but always kept close to other Hopis from her community. At the end of the interview, I asked Bessie if she remembered any of the Hopis who joined her in Riverside. I thought she would perhaps mention a few people, but amazingly she spent the next several minutes naming every Hopi student by village, beginning with students from Bacavi.

I was not surprised when Bessie recalled the names of each Hopi student according to their village. Bessie and her peers originated from close, tightknit communities where they established and reaffirmed their identity as Hopi people by their clan and village affiliations. In the 1920s, Hopis traveled to Southern California from one of twelve autonomous villages on three mesas in northeastern Arizona. Some came from Walpi on First Mesa, Shungopavi on Second Mesa, and the ancient village of Orayvi on the southernmost tip of Third Mesa. Still others left for school from the small farming village of Moencopi near Tuba City, Arizona. Although every Hopi who attended Sherman had a close affiliation with the school, they never lost their association with their village.

I used most of my research in the Museum’s vault to write a dissertation, articles, and eventually a book. But just before I graduated from the University of California, Riverside, I had an unexpected opportunity to co-produce a thirty-minute documentary film on the Hopi boarding school experience that I titled Beyond the Mesas.[10] I co-produced the documentary with film director Allan Holzman, a retired medical doctor from Pennsylvania named Gerald Eichner, and members of the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office.[11] Once again I traveled back home to interview Hopis who went to off-reservation Indian boarding schools, including the Phoenix Indian School, the Ganado Mission School in Arizona, and Sherman Institute. The Museum’s vault played a major role in the production of Beyond the Mesas: Holzman and I spent several hours filming black and white photographs in the vault’s Veva Wight Photograph Collection for inclusion in the documentary. Wight was a Protestant missionary who led Bible studies and other Christian activities at the school. She served as one of the school’s “Religious Workers” during the 1920s and 1930s. One of the photographs that we used showed twenty Hopi girls kneeling and standing near the school’s flagpole. Another photograph was of two Hopi girls embracing each other in front of the school chapel.

My experience at the Sherman Indian Museum has left a lasting influence on me as a Hopi person. I learned the value of working together with many individuals associated with the Museum, students and faculty at the University of California, Riverside, and my community on the Hopi Reservation. Although a growing number of students and scholars, including myself, have had the privilege of basing their research on documents and other items housed in the vault, many more studies have yet to be conducted.[12] The vault is not finished sharing the voices of those students who left their families and homes to attend Sherman. Their stories of assimilation, resistance, and accommodation still remain in the Museum. They wait for the next wave of researchers to release their voices so others might hear. This was the most rewarding aspect of conducting research in the vault. It is also the purpose of our book and the reason why Lori has kept the vault open to researchers of the past and will continue to keep it open for those students and scholars of the future.

Excerpted from The Indian School on Magnolia Avenue: Voices and Images from Sherman Institute, published by Oregon State University Press.

About the Editors

Clifford E. Trafzer (Wyandot) is professor of American History and the Rupert Costo Chair in American Indian Affairs at the University of California, Riverside. He has written and edited several books, including Boarding School Blues, Native Universe, and Death Stalks the Yakama. Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert (Hopi), an assistant professor of American Indian Studies and History at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, is the author of Education beyond the Mesas: Hopi Students at Sherman Institute, 1902-1929 (University of Nebraska Press) and co-producer of a thirty-minute documentary filmm on the Hopi boarding school experience called "Beyond the Mesas." Lorene Sisquoc (Cuhilla/Apache) is Curator of the Sherman Indian School Museum in Riverside, California. She teaches Native American Traditions at Sherman Indian High School and is co-editor of Boarding School Blues: Revisiting American Indian Educational Experiences.

Notes

1 Jean A. Keller, Empty Beds: Student Health at Sherman Institute, 1902-1922 (Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2002), xv.

2 I write at length about Philip Zeyouma in my article on Hopi runners. See Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert, “Hopi Footraces and American Marathons, 1912-1930,” American Quarterly, Vol. 61, No. 2 (March 2010), 77-101.

3 The Sherman Bulletin, January 27, 1909, vol. 3, no.

4. Sherman Indian Museum, Riverside, California.

4 The Sherman Bulletin, March 3, 1909, Vol. 3, No. 9.

5 I write more about this in my book on the Hopi boarding school experience at Sherman Institute. See Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert, Education beyond the Mesas: Hopi Students at Sherman Institute, 1902-1929 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), x. xi.

6 Hopi teacher and author Polingaysi Qoyawayma (Elizabeth Q. White), who attended Sherman from 1906 to 1909, refers to the Riverside area as the “land of oranges.” See Polingaysi Qoyawayma (as told to Vada Carlson), No Turning Back: A Hopi Indian Woman’s Struggle to Live in Two Worlds (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1964), 57.

7 Samuel Shingoitewa interview, Upper Moencopi, Arizona, Hopi Reservation, July 8, 2004. Samuel is the father of Hopi Tribe Chairman LeRoy Shingoitewa of Upper Moencopi.

8 The only complete collection of The Sherman Bulletin is housed in the Sherman Indian Museum vault.

9 Bessie Humetewa interview, Bacavi, Arizona, Hopi Reservation, July 8, 2004.

10 For more information on “Beyond the Mesas,” see http://beyondthemesas.com.

11 These members included Leigh J. Kuwanwisiwma, Director of the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, and Stewart B. Koyiyumptewa, Archivist of the Hopi Tribe.

12 For example, several letters and invoices involving the transportation of American Indian students by railroad remain in the vault. A dissertation or book on the ways government officials used trains to transport students to Sherman Institute, and how railroads fit within the overall attempt to assimilate Native people, is an examination that would benefit immensely from the Museum’s documents.

Related Titles

The Indian School on Magnolia Avenue

The first collection of writings and images focused on an off-reservation Indian boarding school, The Indian School on Magnolia Avenue shares the fascinating story of...