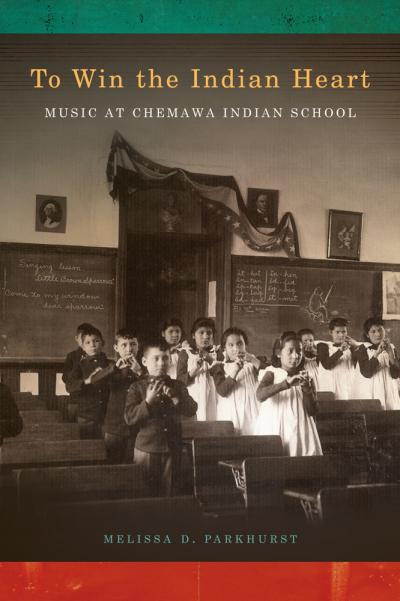

Chemawa Indian School in western Oregon, one of the nation’s oldest federal boarding schools and the longest still in continuous operation, is an emblem of a system that has intimately impacted countless lives and communities. In her new book, To Win the Indian Heart: Music at Chemawa Indian School, out last month from OSU Press, Melissa Parkhurst records the history of the school’s musical life. As Parkhurst worked on the book, she serendipitously relocated to Forest Grove, Oregon, Chemawa Indian School's original location.

Today on the blog, Parkhurst reflects on this unique experience—what it was like encountering her research in her day-to-day experience, as well as in the historical fabric of her community.

***

Chemawa alumnus and musician Max Lestenkof (Aleut, class of 1969) articulated: “you make a complete circle in life, when you do music.”

One of the full circles I personally traveled happened by accident. While working on the research for To Win the Indian Heart, I took a job teaching in the Music Department at Pacific University, in Forest Grove, Oregon. Forest Grove, a small city in the Willamette Valley, about 25 miles west of Portland, was the original home, 1880-1885, of the school that would become Chemawa. Several catastrophic fires shaped Forest Grove’s early history, and it was a fire that destroyed the girls’ dormitory, causing enough damage to bolster the case to move the school to its current location, just north of Salem, Oregon.

Walking the Pacific University campus and the streets of Forest Grove, I wondered, what remnants of the original campus might still be present? Would the residents of Forest Grove have any sense of the Indian school as part of their community’s history? And if the earliest students of Forest Grove Indian School could talk with us today, what might they say of their experiences of music and the school?

Lecture notes from Rick Read (an esteemed former archivist at Pacific, now deceased) suggest tantalizing evidence that a single building from the original campus existed as late as the 1990s and may still be standing today. Despite many hours spent with town historians, plat maps, and the streets themselves, I’ve become convinced that the original campus is likely gone.

Some town residents, particularly members of the Friends of Historic Forest Grove, are keenly aware of Forest Grove’s role as the original site of the school. Early school newspapers are kept in the archives of FHFG and of Pacific University, as are transcripts of locals’ remembrances that span the early 20th century.

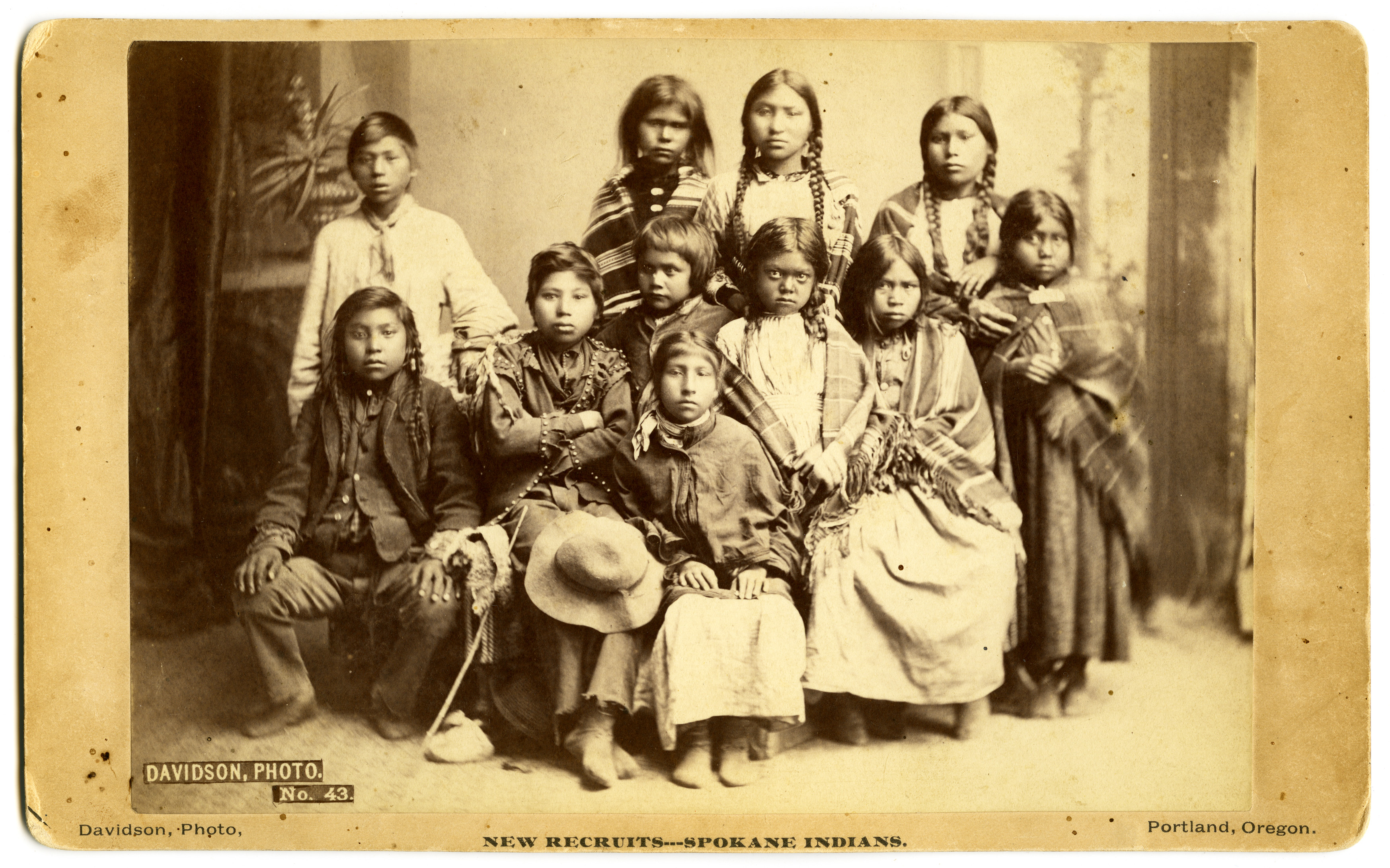

Of the students themselves, we see the early “before and after” photos circulated to suggest the students’ profound transformations at the hands of the school’s assimilationist campaign. More privately maintained were the records of many students’ early deaths while at school, as they faced new diseases while living in a foreign setting. Also, we know now that—despite the photos—most of the school’s early attendees already had some familiarity with Euro-American culture, through their interactions with settlers, missionaries, and Indian agents in their home communities.

In the early campus newspapers, which served as promotional materials for the school, we see administrators’ accounts of school bands, though we do not know the extent to which membership in the early bands was compulsory or voluntary. Letters from alumni who proceeded to work at other Indian schools as music teachers are perhaps the first evidence that music could be life-giving for some students, offering a source of joy, competence, and sometimes even a livelihood.

Despite the school’s attempts to erase all aspects of the students’ Indian identity, the story of music at the Forest Grove Indian School involves both strength and agency, with some students using their musical training to bond with each other, sustain themselves, find teaching jobs, and share their craft with other young Indian people. In my book, I chronicle the subsequent phases of music instruction, as the school moved to its current location in 1885 and came to enroll as many as a thousand students at a time.

Chemawa Indian School stands today as the nation’s oldest continuously operating Native American boarding school. It has abandoned its assimilationist mission, becoming instead an institution that encourages Native American students to take pride in their heritage. By engaging in school bands, choirs, dances, pageants, garage bands, and powwows, students mine sources of resiliency that help many to survive and bounce back from the hardships of school and life after Chemawa.

—Melissa D. Parkhurst

You can order To Win The Indian Heart here.

Melissa D. Parkhurst is an instructor of music at Pacific University in Forest Grove, Oregon, where she teaches courses on World Music and Music History. She earned a doctorate in ethnomusicology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her current research interests include First Nations music in the Pacific Northwest, how music promotes personal and community resilience, and the role of music in cultural revitalization.

Melissa D. Parkhurst is an instructor of music at Pacific University in Forest Grove, Oregon, where she teaches courses on World Music and Music History. She earned a doctorate in ethnomusicology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her current research interests include First Nations music in the Pacific Northwest, how music promotes personal and community resilience, and the role of music in cultural revitalization.

Photographs courtesy of Pacific University Archives. For more images from the early Forest Grove Indian Training School, please visit the university's digital exhibits.

Related Titles

To Win the Indian Heart

Since 1879, Indian children from all regions of the United States have entered federal boarding schools—institutions designed to assimilate them into mainstream society. Chemawa Indian...