DJ Lee’s Remote: Finding Home in the Bitterroots takes readers on a journey not only through the Selway-Bitterroot wilderness but also through history, acquiring access to family legacies, and recovering selfhood in a time of loss. In today’s blog, Lee’s colleague, Peter Chilson, a literature and writing professor at Washington State University, interviews Lee about her writing process and how her emotional connection to the Selway-Bitterroots enabled her to persist through the challenges of her journey.

*****

Chilson: Your book starts off with your friend Connie’s disappearance. Can you talk about that?

Lee: I’ve been actually writing this book for fifteen years, and going back into the  wilderness, really in search of my grandparents’ story. I was in the midst of getting the manuscript into shape when my parents called and told me that Connie had gone missing and I couldn’t believe it. Connie Saylor Johnson knew the Selway-Bitterroot more than almost anyone. She helped me learn the trails, I hiked back there with her, visited her, we corresponded. I went back several times and she showed me documents about the history. So on a very physical level, but also a scholarly and intellectual and on a spiritual level, she was super important to the book. And to me--so when she went missing, it was devastating. It was devastating for me and hundreds of people who loved her. Because she was such an important part of my book and the process itself, I had to start from scratch and rewrite the book to incorporate her disappearance.

wilderness, really in search of my grandparents’ story. I was in the midst of getting the manuscript into shape when my parents called and told me that Connie had gone missing and I couldn’t believe it. Connie Saylor Johnson knew the Selway-Bitterroot more than almost anyone. She helped me learn the trails, I hiked back there with her, visited her, we corresponded. I went back several times and she showed me documents about the history. So on a very physical level, but also a scholarly and intellectual and on a spiritual level, she was super important to the book. And to me--so when she went missing, it was devastating. It was devastating for me and hundreds of people who loved her. Because she was such an important part of my book and the process itself, I had to start from scratch and rewrite the book to incorporate her disappearance.

Chilson: That’s a compelling story. I read the book and you talk about Connie being not only important to you but key to your understanding of what wilderness is all about. Can you talk more about that?

Lee: I think with the things I learned from Connie and that everybody learned from her is that wilderness is something almost mystical. It’s the solid trees and rocks and water and wild animals and stewardship of the land, but it’s also something bigger than the sum of its parts. Connie really gave people not just the physical being in the place but also the way that it contributes to your soul.

Chilson: Another character in this book who knew Connie but whom I also find very compelling is Dick Walker. I’m a student of the French writer [Antoine de] Saint-Exupéry, who was also a pilot like Dick. Saint-Exupéry spent all these years criss-crossing the Sahara delivering the mail in the French African colonies during the 1920s. He also flew the mail across South America in a plane very much like Dick and you flew together  over the Selway-Bitterroot wilderness. That’s part of what I bring to your book as a reader. Your book seems rooted in the stories of these kinds of people. Dick Walker is this compelling, visceral character, and so is Connie, and there are people in the book that have names like Puck. These people have real, hard substance They’re golden characters for a story. How do you find these people and get them to talk to you?

over the Selway-Bitterroot wilderness. That’s part of what I bring to your book as a reader. Your book seems rooted in the stories of these kinds of people. Dick Walker is this compelling, visceral character, and so is Connie, and there are people in the book that have names like Puck. These people have real, hard substance They’re golden characters for a story. How do you find these people and get them to talk to you?

Lee: Well, you probably remember the part about meeting Dick for the first time, I learned his name from a forest service archeologist who told me I should get in touch with Dick Walker. The way the person described Dick, I got an image in my mind of some kind of hermit living out in the woods, which he does. He lives up on a mountaintop. But even just hearing about him, he was a frightening kind of figure for me. The archeologist said that he had a lot of documents and history stored in his house. I was looking for information about my grandparents. So finally I drove to his house, up this mountain, dirt road, and he was kind of frightening to me at first, but I just spent time with him and was open to everything he had to teach me and made a fool of myself again and again and again because I didn’t know anything about the wilderness. Some of the conflicts that we had are detailed in the book, but besides Connie, Dick was one of my greatest teachers.

Chilson: Can you tell us a little bit about the process of writing the book and how that has changed you?

Lee: This is where my family story comes in and where it transitions from history and on-the-ground research to memoir. On my grandmother’s deathbed, she gave me this box that was full of documents and letters and photographs about the Selway-Bitterroot. At that point, I had no idea that this place even existed. I heard the word ‘wilderness’ once or twice in my childhood, but I was in my mid-thirties when my grandmother passed away. She was very important to my life, but my mother and I had a conflicted relationship just as my grandmother and my mother had, so I felt compelled to go to the Selway-Bitterroot wilderness. I was very trepidatious. I didn’t want to step on toes. I didn’t want to hurt my mother by trying to find out more about the family history than I should have known. I didn’t want to uncover dark secrets that would hurt people, but at the same time I wanted to. I couldn’t help it. I’m an archivist and scholar and historian. When I found that box of letters and documents and photos, I had to pursue it. I think the greatest change—or maybe the one most important to me—is that through that painful process of going back again and again, sometimes with my mother also was going back there and my father and other members of my family, my mother and I started off, in my mind, kind of competing for information and family memories, but by the end we were walking hand in hand. The land itself and the journey changed us.

Chilson: So your mother was a willing participant in your research?

Lee: She was. Sometimes she didn’t know she was. My grandmother had some mental illness and that was kind of hard for my mother and I to start talking about, but I asked her and she would open up. At some point, I told her I was writing this family story and she said, “You write what you need to write. It’s your story.” That was a big moment for me, so I’d say she’s a willing participant cautiously.

Chilson: I know a little bit about the Selway-Bitterroots. I hiked into it a few times myself. Both alone and with other people including you and your family at least once. It’s one of the most beautiful—and at the same time foreboding—wilderness places I have ever been to in my life. High-peak mountains, rattle snakes, wolves, beautiful rivers. It’s an incredible place. But you came to this wilderness as a scholar, as somebody who really wasn’t that experienced in hiking in the backcountry. How did you acclimate?

Lee: It was hard. I grew up in Seattle. I spent many years in Calgary, Alberta. I lived in London for a bit. I’m a city person. I had this odd confidence that I could just do this. Like why not? Like of course. But it was physically really difficult for me. My very first trek in was so difficult I almost turned back and I would have if it would have been easier to turn back. There were other times where it was hard for me to be back there just physically. I mean blisters and scrapes and wild animal encounters and trail finding. A friend and I almost drowned in a rushing creek called Bad Luck Creek in late May one year. We were doing a fifty-mile hike down the Selway River, total wilderness, and we almost drowned. It was very frightening...And then like flying in fogs a couple of times with the plane getting really squirrelly. There were also times when I was really searching for my grandparents when I was there by myself and then after Connie went missing, I’d been camping there by myself all fall— I just felt very comfortable there. After she went missing, I physically felt okay, but psychologically and spiritually I felt a disturbance and it was hard for me to be there sometimes. I feel like I’ve acclimated, but I don’t know if I’ll ever feel 100 percent at home there and I think that’s a good thing. I think a wilderness should not be a place where you feel comfortable like you’re sitting on your couch in front of a TV. You should always feel a little bit challenged.

Chilson: You write about the place with a great deal of respect. I think that comes from, in regard to wilderness, a certain amount of fear. That being said, we’ve been talking a lot about your own story within the wilderness and Connie and Dick and your mother, but you also weave in a lot of history. Lewis and Clarke, the history of the forest service, homesteading, and the Nimíipuu. How did you strike a balance between these different layers of history and your own story?

Lee: That’s a good question, because at first there was no balance. It was all history and context...My own story was not important to me at first. I was really interested in my grandparents, but I denied the personal part. I thought they were only historical subjects. I’ve written about a lot of authors and historical characters from the early nineteenth century, so I just approached them as historical characters and the place as a place that I just had to contextualize in terms of geological history, indigenous history, the history of colonial settlement, and all the different stakeholders that have passed there throughout the years. Maybe about seven years in, I realized that this was my story. I always kept a journal. I’ve been a journal and diary keeper since I was seven years old, so I had all of these personal notes too, and I realized that my story was intimately wrapped up with the story of this place. I did a lot of personal writing in the later draft of the book, but the first drafts were mostly historical….I realized that, when I started doing the first edits, that a little bit of scholarship goes a long way, so I had to learn a different kind of writing. I had to learn a writing that braided the history and the personal in a much more intimate way than I was used to.

Chilson: You do have all of these scholarly books in your past. You’re a scholar of the great romantic poets and you’ve done a lot of that type of writing. Was it difficult to make the transition from scholarly, third person, formal writing to memoir?

Lee: Yeah. It was. I think the topics are similar. Of course I love the British romantic poets like Woodsworth and Blake and Keates and Coleridge and the novelists Jane Austen and Mary Shelley. But my first book was about the slave trade and British poetry, so I’ve always been interested in these social justice topics and these histories that have maybe not received as much attention as the great artistic movements and I like bringing those two together. That mode of braiding came naturally to me. The technique itself was really hard for me. I’m not saying this is a general rule, but for me personally it was hard to learn a way of writing that was much more intimate and honest and close to the bone. It’s a difficult thing for some scholars to go to that deep on personal level and find language for it that you’re willing to put into writing. That’s something I had to learn.

Chilson: One of the historical narratives within the book that you explore is the history of the Nimíipuu in this particular wilderness. I’m wondering how you did that research. There are human characters involved in that story, some of whom you met in your life. I’m wondering how you blended the historical research with the human characters.

Lee: My grandmother was a good friend with a Nimíipuu elder. They grew up together on the edge of the wilderness. They went to school together and kept in touch. When I met him I was in my twenties. He made a very strong impression on me. He had a really deep, kind of commanding voice, but a really gentle manner. I guess what really struck me is the way he and my grandmother talked about people they knew just like you’d gossip with your friend in junior high school, but they were in their eighties. I really liked observing their friendship and hearing them talk about the old times. But one time when I was visiting them, they talked about what I later realized was the wilderness. They both had stories and lives back there. I did know some about the Nimíipuu, but I did a lot more research. I spent probably an entire year in this history. I read all of the accounts of General Howard. I read the first New York Times article criticizing the Nez Perce war of 1877. Later I went back with this archeologist and he told me about how the Nimíipuu had lived. A lot of that didn’t make it into the narrative because it’s been told by other people, but it was a really important story to me. It’s a really important story for the land. I mean the land is the Nimíipuu’s land. It doesn't belong to the National Forest Service or the Wilderness Preservation System of the US government. I consider it Nimíipuu homeland to this day. I think it always will be. As long as this earth is here, it will always be Nimíipuu land.

Chilson: In my reading of the book, I noticed that there’s a real gender balance here. There are a lot of major male characters in the book as well as major female characters, but to me the women in the book are the governing characters of the story. Do you see the book as making the contribution to the subject of women in environmental history in the United States or women in the wilderness?

Lee: I very much do. I see it as a book about women in the wilderness. Connie, for example, is the spirit of women in the wilderness. There’s also my grandmother who was back there for twelve years off and on and had a very conflicted relationship with the wilderness. There’s my mother, too. I’m not going to give you a spoiler—you know it—but she’s very comfortable back there. My mother is more comfortable back in the wilderness than almost any woman I’ve seen back there. Of course there’s me, but there are also a lot of other women. One of my favorites is a woman named Amy. I’d met her early on but I also reconnected with her after Connie was gone. She has to be one of my favorite wilderness women. There are so many other women that I wasn’t even able to write about like my friend Marg, who’s an amazing horse woman and a mule wrangler. There’s my friend Hannah who packs back there and rides back there.

Chilson: You mention the photograph of Amy which I noticed because it’s from the present day. It’s probably a photograph you took. Because so many of the other photographs are from history. I’m wondering how did you select the photographs and, even more importantly, where did you find them. Were they a part of the family archive or did you do more detective work to find them?

Lee: Some of them came from Dick Walker. He’s an archivist himself. He collected thousands of Selway-Bitterroot photographs. It’s an amazing collection. Some of them came from the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest archeologist and some of them I took. I was very fortunate because the publishers let me have twenty-eight photographs. The photographs tell a story separately. Some of them illustrate chapters, but if you line them all up, they also tell their own narrative. They interweave into different chapters where you don’t expect them. I wanted the photographs to tell a narrative that was complementary but also separate from the book itself.

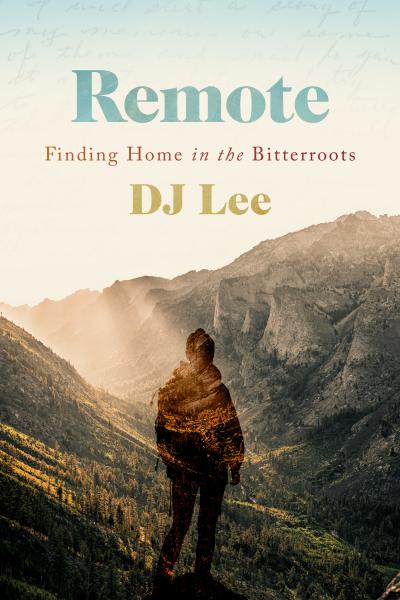

Chilson: I find the book, just the way it’s designed, to be very handsome. The foreboding nature of the wilderness is right there on the cover with the shadowy photograph of the woman looking down into the wilderness. Then we open up the book and we have this beautiful map. Maps like this are really hard to get published in books. How do you go about capturing a sense of this incredible wilderness on the page? I realized it took you a number of years to write this, and that’s part of it, but sitting down at the typewriter: how do you do that?

Lee: Thank you. The map is beautiful. It’s made by a company called Cairn Cartographics in Missoula. I know the woman who made it. Amelia Hagen Dillon. She loves the Selway-Bitterroot, so it was really special to have her make me the map. But yeah, a map is a map. It’s a different kind of imaginative place than it is when you hike it and when you know all the history and when you put your blood, sweat and tears into the place. I think that was one of the reasons why it took me so long to write about this place because it’s such a complex, nuanced place. It’s a mythological place.

*****

DJ Lee is Regents Professor of Literature and Creative Writing at Washington State University and earned a PhD from the University of Arizona and an MFA from the Bennington Writing Seminars. Her creative work includes over thirty nonfiction pieces in magazines and anthologies. She has published eight books on literature, history, and the environment, most recently the 2017 collection The Land Speaks: New Voices at the Intersection of Oral and Environmental History. Lee is the director of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness History Project and a scholar-fellow at the Black Earth Institute.

Peter Chilson teaches writing and literature at Washington State University. He has written four books, including most recently Writing Abroad: A Guide for Travelers (with Joanne Mulcahy). His work has appeared in The New England Review, The American Scholar, New Letters, Consequence, Foreign Policy, Poetry International, Gulf Coast, Best American Travel Writing, and elsewhere.