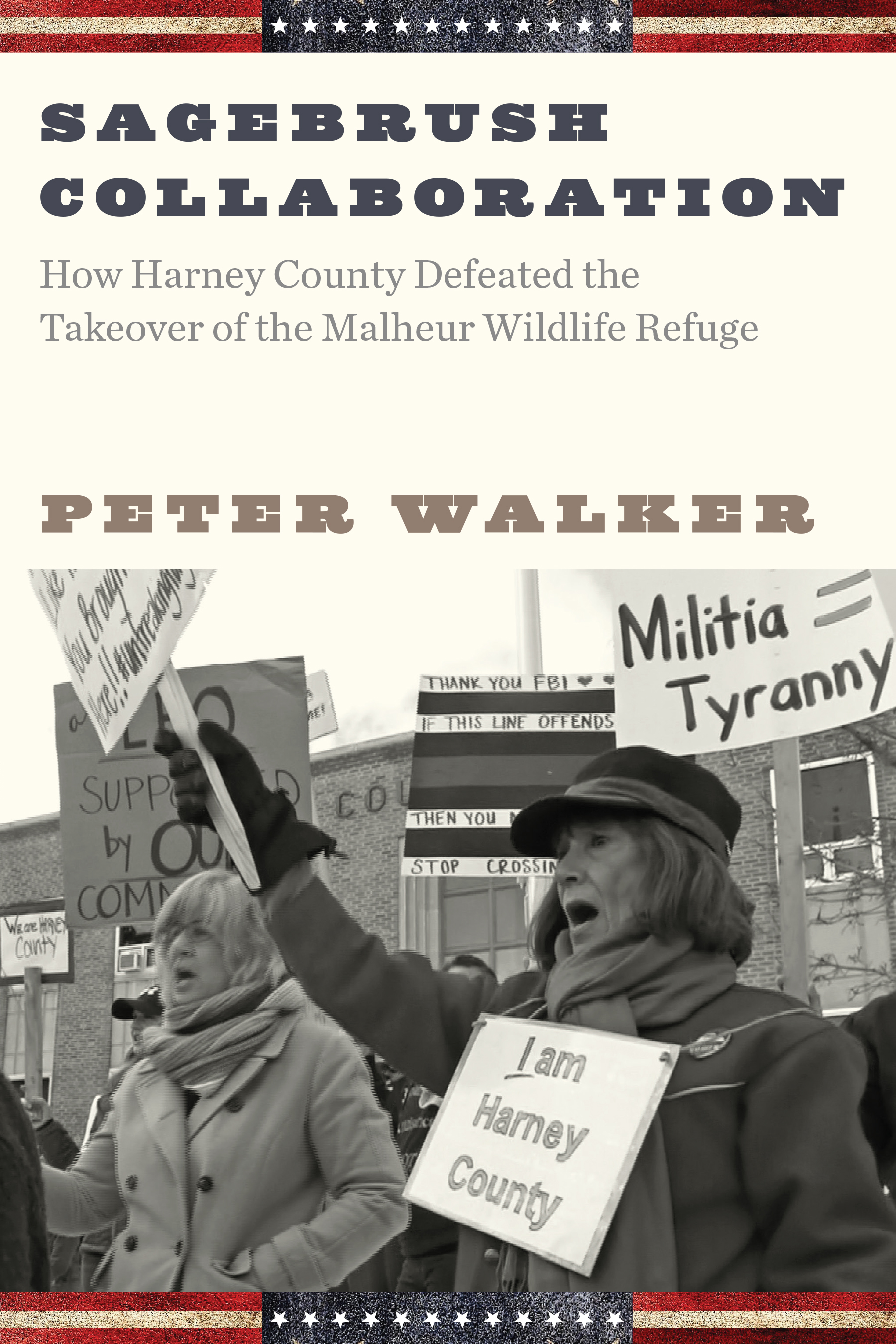

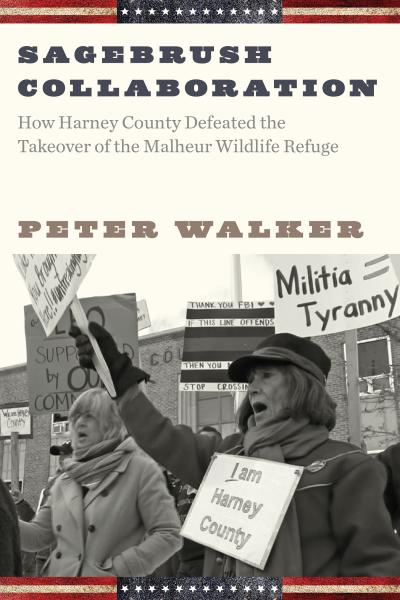

In 2016, armed militants took over the Malheur National Wildlife refuge in Harne y County, Oregon. For forty-one days, they seized the headquarters of the refuge and for three months, they occupied the community led by Ammon Bundy and Ryan Bundy. This month, Oregon State Press published Peter Walker’s Sagebrush Collaboration, the first book-length study of this militant take over. In Sagebrush Collaboration, Peter Walker contextualizes and researches the take over as well as considers the future of America’s public lands. Today on the blog, Walker provides an update about the Bundy's anti-federal revival tour, political ambitions and Harney County efforts to rebuild community.

y County, Oregon. For forty-one days, they seized the headquarters of the refuge and for three months, they occupied the community led by Ammon Bundy and Ryan Bundy. This month, Oregon State Press published Peter Walker’s Sagebrush Collaboration, the first book-length study of this militant take over. In Sagebrush Collaboration, Peter Walker contextualizes and researches the take over as well as considers the future of America’s public lands. Today on the blog, Walker provides an update about the Bundy's anti-federal revival tour, political ambitions and Harney County efforts to rebuild community.

***

Books have a beginning and an end, but the story that I attempted to tell in Sagebrush Collaboration began well before the events of January 2016, and continue to the present day.

Books have a beginning and an end, but the story that I attempted to tell in Sagebrush Collaboration began well before the events of January 2016, and continue to the present day.

In reality, there were two stories. The one I felt most important to tell—the one that virtually all media reports at the time ignored—was about Harney County’s success in building collaboratives that, in the words of one prominent local rancher, “inoculated us from the Bundy disease.” That story can be dated to the late 1990s and the early 2000s, when local ranchers, federal managers, the Burns Paiute tribe, environmentalists and others decided to try cooperative approaches to solving long-standing problems. That effort paid off handsomely when the Bundy family arrived. The Bundys offered solutions based on armed confrontation with federal authorities; but the community had their own solutions—ones built on principles of collaboration. The collaborative approach won, and quietly continues today. I continue to follow it.

The other story—the one that got almost all the headlines, then and now, was about the radical vision and strategy offered by the Bundy family. As it happens, my book ended at almost precisely the time when the Bundy movement shifted to a new phase. I turned in the first draft of Sagebrush Collaboration on December 18, 2017. With the generous permission of my editors at Oregon State University Press, before the book went to print I was able to update a few key events that occurred in early 2018. The most significant of these was the dismissal, on January 8, 2018, of all charges against the main figures in the 2014 armed Bunkerville standoff, due to mishandling of evidence by federal prosecutors.

Immediately, the newly-freed members of the Bundy family publicly declared that their fight was only just beginning. That declaration sent shivers down the spines of those of us who witnessed the trauma of the occupation of Harney County in 2016. What, exactly, would the Bundy family, now elevated to the status of near-mythic Goliath-slaying western heroes, do?

The obvious concern was that the Bundys would initiate new armed confrontations. After all, the takeover of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in 2016 was a direct follow-on from the 2014 standoff at the Bundy Ranch in Nevada in 2014. The Bundys were clearly looking for a way to leverage their success in facing down federal authorities at Bunkerville into a broader anti-federal government movement. Although they failed in 2016 to transfer the Malheur Refuge to local control or ignite a wider anti-government movement, the Bundys gained extraordinary fame and public attention. Those of us who met the Bundys and understood the depth and passion of their anti-federal government ideology had no doubt that, once freed, they would attempt to leverage their greatly enhanced fame into further anti-federal government actions.

To date those actions have not included further armed confrontations—though many of us who have followed the Bundy story closely continue to believe that such confrontations are almost certainly only a matter of time. Instead, for the moment the Bundy family appears to be investing their energy in building a wider base of public support for anti-federal actions.

Whatever one thinks of the Bundys’ political ideology, there is no disputing their industriousness and talent for promoting their cause. On January 20, 2018, less than two weeks after all federal charges against the Bundys were dismissed, patriarch Cliven Bundy (wearing a “Not Guilty!” lapel button) and his son Ryan Bundy spoke to a large crowd in Paradise, Montana. Cliven challenged Montanans to “act like you understand the Constitution.” That is Bundy-speak for resisting federal authority. Notably, this first major public speaking event for the Bundy family after the dismissal of charges against them was organized with support from Montana State Senator Jennifer Fielder, the CEO of the American Lands Council—a group that promotes the transfer of federal public lands and is supported by billionaire anti-federal activist brothers Charles and David Koch. The Montana event was the first of many in which the Bundy family, with support from the wealthy and powerful, would spread their anti-federal gospel.

On their 2018 anti-federal revival tour, the Bundys’ message took on a darker and more overtly religious tone. On April 22, I attended an event in Modesto, California, sponsored by oil tycoon Forrest Lucas’ organization Protect the Harvest, at which Ammon Bundy accused the federal government of being controlled by environmentalists whom Bundy described as “enemies of humans” and of God. Bundy specifically and repeatedly called out by name one specific environmentalist leader, who he accused of worshipping “Baal,” a false god in Bundy’s view. Calling out a specific environmental leader as an enemy of humans and God appeared to invite violence against that individual—after all, one knows what to do with enemies of God. The concern is real, given that in 2014 two Bundy supporters at the Bunkerville standoff gunned down two police officers in Las Vegas, pinning a note on one of the bodies declaring the murder “the beginning of the revolution.” If not intentional invitations to violence, the Bundys say nothing to discourage such ideas among their more unstable supporters.

Hints of violence have been present in almost all of the speaking events by Cliven, Ammon, and Ryan Bundy in 2018, consistent with the unofficial but explicit Bundy family motto, to do “whatever it takes” to achieve their anti-federal political goals. On May 26, 2018, I attended a speech by Ammon Bundy in Yreka, California—home to the anti-government State of Jefferson movement—in which Bundy encouraged supporters to “stand” in defense of their water rights not in the courts but “there at the diversion.” It was an echo of the events of the early 2000s when angry farmers whose irrigation water had been shut off used chainsaws and blowtorches to seize water in the Klamath River that had been reserved for endangered salmon and local tribes. When a local organizer introduced Ammon Bundy to the Yreka audience, she recounted a conversation with Bundy by phone in which he agreed to come only if anti-government locals were “ready to stand”—meaning ready for civil disobedience. In the Bundy worldview, civil disobedience is all but synonymous with armed civil disobedience.

What is most powerful in each of the Bundys’ public performances has been their remarkable and clearly intentional successes in tapping into and stirring up strong emotions. There is no shortage of anti-federal government sentiment in the rural American West. The Bundy family, however, have become masters of transforming long-simmering grudges into a near-frenzied emotional state. At almost every speaking event in 2018, Ammon Bundy, for example, took out various military medals, flags, and uniforms given to him by ex-military supporters during the Malheur Refuge takeover. As Bundy takes out each item, he tells the tale of how veterans bestowed the gifts on him—which he declares that he did “not deserve.” In every instance, tears well up in Ammon Bundy’s eyes and his voice chokes up as he tells the stories. Invariably, tears flow down the cheeks of audience members as well. Tapping into the most potent symbols of traditional American patriotism, Bundy invokes the ideals of armed, patriotic heroism and transfers those ideals onto himself and his cause. And at every opportunity the Bundys invoke the blood sacrifice of slain Bundy supporter LaVoy Finicum—declaring Finicum a martyr for “freedom.” The call for further sacrifice in the cause of freedom is all but explicit.

While navigating toward the same goal of a federal-free, “sovereign” American West, Ammon Bundy’s brother Ryan has taken a different path—making himself an official candidate for the office of Governor of Nevada. It might seem a surprising choice; but not really. During the Malheur Refuge takeover in 2016, I heard Ryan Bundy specifically say that eliminating federal control in the western states cannot be achieved through conventional electoral politics because a single elected official will stand alone and will not be able to get the changes they want. Ryan Bundy is very smart, and it seems unlikely that he actually believes he is going to become governor. Like the Malheur takeover and the Bunkerville standoff, however, Ryan Bundy’s campaign for governor gives him a megaphone to speak to the public. More importantly, I fear that when Ryan Bundy inevitably loses his bid for governor, it will enable him and his family and supporters to say they tried to achieve their goals through conventional political channels. They will almost certainly claim the political system is rigged against them. That would “prove” to their supporters that further radical and potentially violent anti-government actions are necessary—that is, doing "whatever it takes."

Meanwhile, back in Harney County, the pioneers and innovators of non-violent, collaborative problem-solving approaches continue the unglamorous work of re-building community trust and relationships that can enable them to weather possible similar political disruptions in the future. Scholars, including myself, are seeking to understand how Harney County succeeded, and how the positive lessons from Harney County might be applied elsewhere. The ever-industrious Bundy family will no doubt refine their approaches as well. Which of these two stories prevails may literally decide the future of the rural American West.

***

Peter Walker studies the social factors that shape human interactions with the environment, with emphasis on the rural American West, and Africa. After the takeover of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in early 2016, Walker became almost a part-time resident of Harney County while writing this book. A native Westerner, Walker received his doctorate at UC Berkeley and has served on the faculty of the University of Oregon since 1997.

Related Titles

Sagebrush Collaboration

Every American is co-owner of the most magnificent estate in the world—federal public forests, grazing lands, monuments, national parks, wildlife refuges, and other public places...