In her gripping and courageous debut memoir, Tina Ontiveros leaves it all on the page, inviting readers to lean into her experiences as a young girl growing up in and out of logging camps amidst intergenerational poverty and trauma in the Pacific Northwest. rough house has been on the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association Bestseller list for six weeks running and was an October IndieNext pick from the American Booksellers Association. Tracing her story through the forests and working-class towns of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, Ontiveros brings readers along on her journey of love, loss, and finding home.

* * * * * * * * * *

OSU Press: What was the driving force for you to tell your story?

Ontiveros: Tough question! I think an honest answer would be very long and complicated. For one thing, I think this story was held in my body before I wrote it down. In that sense, I’ve been telling it my whole life—or it has been telling me. I think, as I became more educated and gained more financial stability, I was able to let go of the shame you carry when you are poor. That was a gradual process, sort of becoming free to speak. I worked on it, in bits and different forms, for over ten years before I wrote the manuscript that became rough house.

Tough question! I think an honest answer would be very long and complicated. For one thing, I think this story was held in my body before I wrote it down. In that sense, I’ve been telling it my whole life—or it has been telling me. I think, as I became more educated and gained more financial stability, I was able to let go of the shame you carry when you are poor. That was a gradual process, sort of becoming free to speak. I worked on it, in bits and different forms, for over ten years before I wrote the manuscript that became rough house.

Another big motivation for me was my niece. She is sixteen and her single mom struggles with many of the consequences that come with generational poverty. A few years back, I noticed that my niece was carrying shame, just as I had, just as her mother does, for being poor. And I felt like it was my responsibility to tell part of our family story for her. I want her to see the joy and beauty in the struggle. I want her to know that her story will be something she feels proud of someday. I think knowing that can help her set her shame down much earlier than I did.

OSU Press: Class inequities are a constant theme in your book. Can you talk more about how class struggle shaped your life?

Ontiveros: I don’t think there is anything about me that was not shaped by class. When I was a young adult, I did everything to escape poverty. And I thought that meant I had to leave everything about it behind—including most of my family. Now, I think that’s sad. There is so much wrong with the American ideal of pulling yourself up by your bootstraps. The idea that anyone can make their way in the American economy is false. And, because the lie is so pervasive, we automatically shame anyone who fails at this ideal. We shame the poor and that shame was such a presence in my upbringing. So, I thought the cost of becoming educated and middle class was that I had to set down whatever culture was instilled by my family—iron out my language and be watchful of my habits—because those things brought shame. I didn’t realize the shame came from the outside world—not from something that was wrong with my family.

Now, I tend to push back against the idea that I should have to assimilate if I want to participate in academia or live in the middle class. I think there is something we can all learn from families like mine. And I try to share that with my students early, so maybe they might waste less time in pointless assimilation.

OSU Press: There’s much to be angry at or feel resentful towards in your book, but you come across as very calm in an almost understanding way. What do you do with your anger? How have you processed the difficult emotions described in rough house?

Press: There’s much to be angry at or feel resentful towards in your book, but you come across as very calm in an almost understanding way. What do you do with your anger? How have you processed the difficult emotions described in rough house?

Ontiveros: In the book I write a little about that. In my teens and early twenties, I did have more anger. It has slipped away with distance but also, the process of writing helped me transform that anger, I think. Also, it’s important here to point out the vast difference between writing and publishing. Each writer has to decide for herself what she is ready to share with the world. For me, I don’t think I have any business publishing a memoir if I have not yet processed the anger out of the events I am writing about. I love literary memoir and I notice that, in the memoirs I consider worth reading and rereading, the writer has enough distance to allow her to at least try to see the motivations of others, even those who hurt her. So, it was important to me that I write this book without anger. In the end, the memoir is a thing I created—it is not my life. They are related but not the same thing. And I created this thing to hopefully be able to connect to other people, outside the boundaries of space and time. In order to do that well, it couldn’t be written from a place of anger. It had to be written from a place of curiosity. That is what leaves the story open for others to experience. Curiosity is an invitation.

OSU Press: You spent a lot of time outdoors. How did nature play a role in your life? Was it a source of escape or happiness for you?

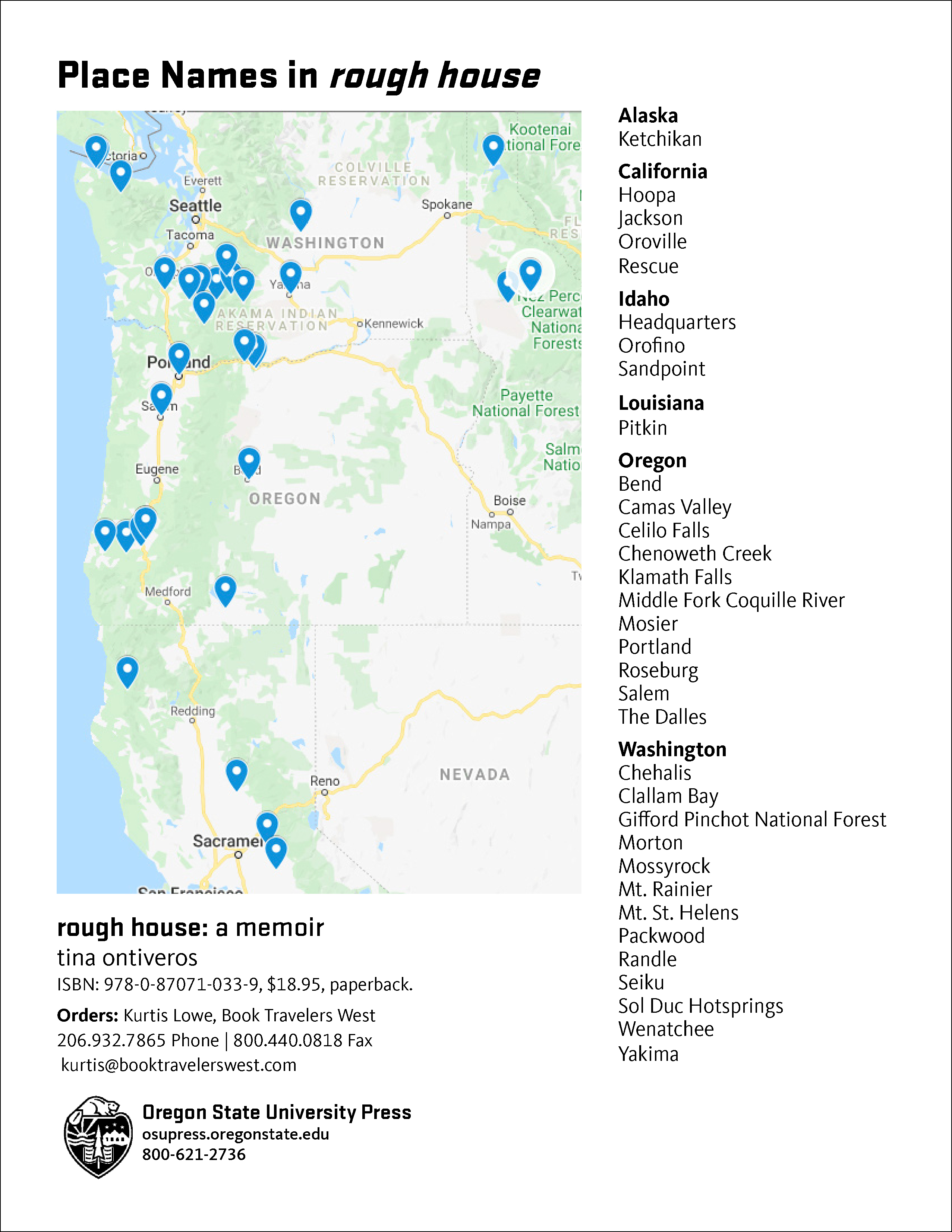

Ontiveros: Yes—my dad was a migrant logger so we moved constantly, but we always lived in or very near the woods. I had this beautiful and wild backdrop for all my childhood stories and that made life with him take on a fairytale quality. After my mom left him, every time I came back to my dad, I returned to the woods. Hardly ever the same woods—he was always on the move even after he stopped logging. But still, it was always a journey of returning to the forest. That really helped me sort of think of my dad as a mythological figure and I think it also helped me, as a child, process some of our trauma. Because there is always danger in fairy tales—they wouldn’t be complete without that darkness. Adventure comes with risk.

Also, my dad had a way of celebrating beauty through nature, of teaching me to be curious in wandering and exploring. Those gentle moments really balanced out his more troubling behavior. So, I wouldn't say nature was a source of escape. But it was a source of comfort in that it allowed me to find beauty in some very hard times. I also think there is a way that being in open spaces, being in the natural world, reminds you how small and insignificant you are. And that’s true of your troubles as well. So, I do think there is a way that the spaces I was lucky to sort of wander through with my dad might have given me some perspective. Nature is always demonstrating that nothing is permanent. Coastlines and the forests are always changing. That’s true of our sorrows, too. Tomorrow, or the next day, they will be transformed.

OSU Press: You migrated all throughout the PNW. Are there any particular spots that were your favorite to live in or any specific areas in the PNW that were special to you?

Ontiveros: Packwood is my favorite of all the places I lived with my dad. That seems strange because my worst trauma happened there. But it was also a place where I experienced great joy and learned so much about resilience and my own strength.

The Dalles is also very close to my heart. I will always consider it my home, though I no longer choose to live there. The Dalles is hard for me in so many ways. It is brown and dry; I prefer green and rain. There’s so much history there for me, much of it painful. It's a working-class town and I had this idea I wanted to be “more.” I wanted to be educated and financially secure. I often felt misunderstood and like I just wanted to get out. But it is also where my mom is, where my bookstore is. It is the place where so many things that really are the heart of me live. And I can always feel there are people there, cheering for me no matter what. So, I will always come back. And, like all things, distance has given me appreciation for it.

The Dalles is also very close to my heart. I will always consider it my home, though I no longer choose to live there. The Dalles is hard for me in so many ways. It is brown and dry; I prefer green and rain. There’s so much history there for me, much of it painful. It's a working-class town and I had this idea I wanted to be “more.” I wanted to be educated and financially secure. I often felt misunderstood and like I just wanted to get out. But it is also where my mom is, where my bookstore is. It is the place where so many things that really are the heart of me live. And I can always feel there are people there, cheering for me no matter what. So, I will always come back. And, like all things, distance has given me appreciation for it.

OSU Press: If you could tell young Tina anything, what would it be?

Ontiveros: Honestly, I don’t think I would tell her anything. Like I say in the book, I have to leave her alone in moments of trauma—she has to figure it out on her own, so that I can be made. And I can see now how everything she needed to know was given to her—she just didn’t always listen. My dad used to say to me, if I was in pain and wanted him to somehow make it better, that I just had to wait. His phrase was, Ain’t nothin’ for it but time. The pain was going to pass with time. Another thing he sometimes said was, If I ain’t hurtin’, I ain’t livin’. He had troubling behavior, that’s for sure. He was the product of generations of poverty and that has a way of making some people hard. But he was always showing me how you get back up and try again. If young Tina could have understood the wisdom in that, she might have been spared a lot of anxiety and heartache. But the message was always there for her—she just had to be open to receive it.

###

Can’t get enough of rough house? Hear from Ontiveros herself, as she delves into the process of making rough house and the trials and tribulations of her childhood in the book trailer. Watch here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kal0WogZ-c

Tina Ontiveros is a writing instructor at Columbia Gorge Community College, book buyer at Klindt’s Booksellers in The Dalles, and current president of the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association.

Related Titles

rough house

Tina Ontiveros was born into timber on both sides of the family. Her mother spent summers driving logging trucks for her family’s operation, and her...