The history of the Industrial Workers of The World (IWW) is a fascinating story of a radical labor movement in the 1900s. The members were referred to as “Wobblies” and fought tirelessly for social justice. While historians have focused on this movement and their work, the role of women in the IWW has long been overlooked.

The history of the Industrial Workers of The World (IWW) is a fascinating story of a radical labor movement in the 1900s. The members were referred to as “Wobblies” and fought tirelessly for social justice. While historians have focused on this movement and their work, the role of women in the IWW has long been overlooked.

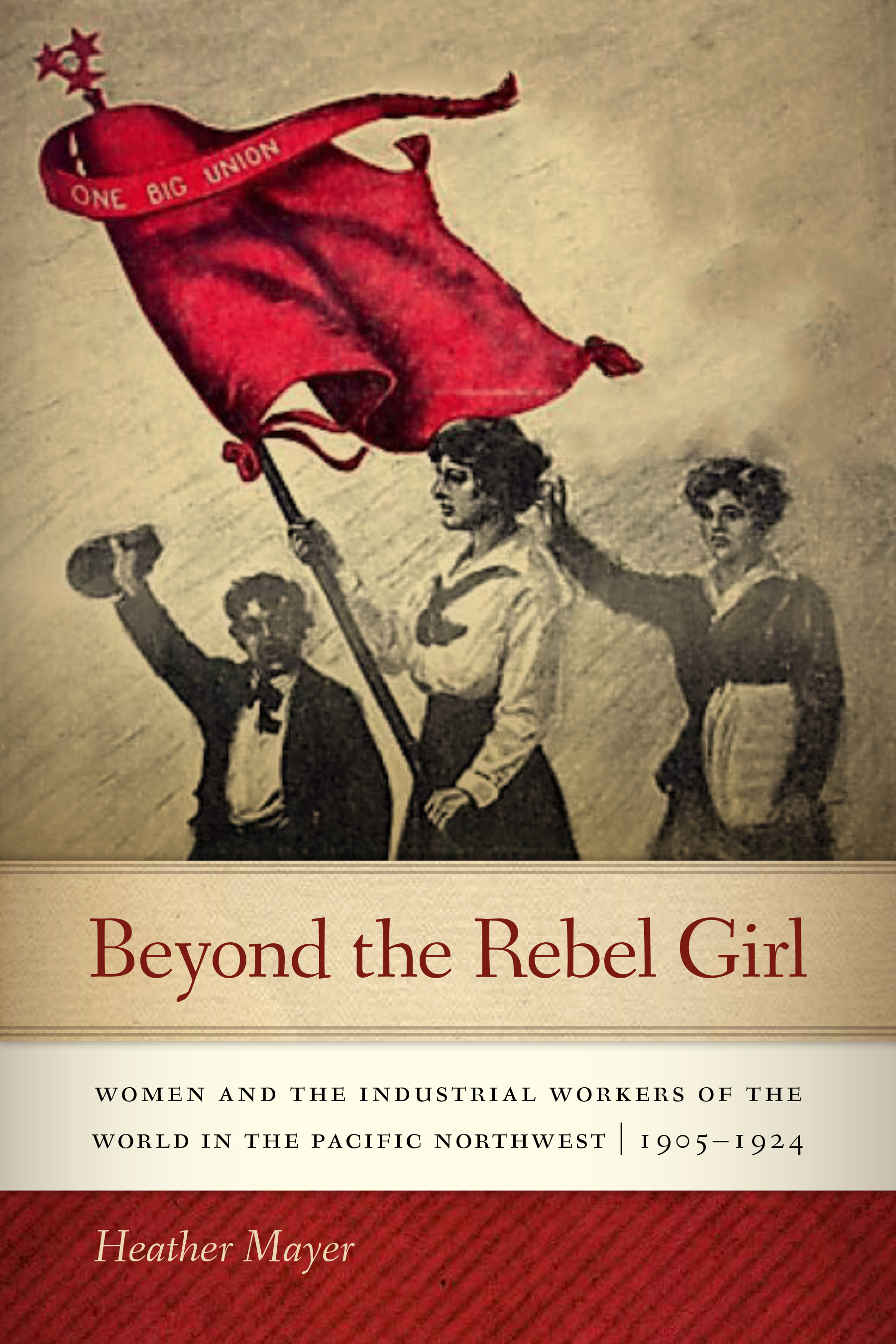

Heather Mayer researched the role of women in the IWW and compiled what she discovered in Beyond the Rebel Girl, one of our most recent titles. In this interview, Meyer shares her experience of conducting this important research, learning more about key figures in the movement, and the origin of her interest in radical history. This interview was conducted through email with Zoë Ruiz and Carolyn Supinka, our Griffis Publishing Interns.

Heather Mayer will be at Powell's on Wednesday November 28.

***

ZOË RUIZ: In this book, you’re challenging the predominantly male and masculine narrative about the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in the Pacific Northwest. While IWW members are often depicted as young, single, and male, Beyond the Rebel Girl widens the lens and includes the history of members who were women. There were many members who were wives and mothers in the group. How did women who were wives and mothers, who had familial responsibilities, make a significant impact on IWW in the Pacific Northwest?

HEATHER MAYER: They had an impact in ways that I think have been easy to overlook. For example, in 1908 Wobbly Joe Walsh helped to organize the “Overalls Brigade” of hobo Wobblies who hopped trains from out west to join the national convention in Chicago. It’s a pretty standard story in the history of the union. But when I was reading an article in the Industrial Worker, they noted that his wife, Dollie Walsh, joined them and helped to organize meetings along the way. That’s pretty important to their success, and yet often goes unnoticed. Kate MacDonald edited the Industrial Worker when her husband was arrested. Edith Frenette arranged for boats to take Wobblies into Everett during the free speech fight. Women brought food and supplies to men in jail. Women with families couldn’t always risk arrest by speaking on the street, for example, but they could help with fundraising and spreading information about what was happening.

CAROLYN SUPINKA: Can you share about your experience researching the role of women in the Wobblies? What was it like researching a group that has been overlooked?

HEATHER MAYER: For my first big research trip, I was really excited to visit the Reuther Library at Wayne State University when the Industrial Workers of the World collection is held. They have 180 boxes of material, and I came away from that trip with maybe a few sentences that I used in the book. No wonder the previous histories of the union didn’t say much about women! I also realized that I was going to need to be a lot more creative in my research.

ZOË RUIZ: I’m curious about your historical research of the Everett Massacre and the Tracy Trial. In the book, you write, “The Everett Massacre is one of the most infamous events in the history of the IWW, but little investigation has been made into the role women played in the events…” How was this experience for you in terms of research and writing? Did what you discover through your research surprise you?

HEATHER MAYER: Studying the Everett Massacre is really where I started to think that there might be more to the story. When you read Wobbly Walker C. Smith’s book The Everett Massacre that came out in 1917, there were photographs of women at the funerals--there were 18 female pallbearers. Women testified during the trial, and Edith Frenette, one of the women, was portrayed as the ringleader by the mayor of Everett. It seemed like there was a story there, and the more I dug in, the more I found. But for every lead I was able to follow, there were a lot of names like Mrs. Smith or Mrs. Jones that I couldn’t find any more information about, which was, of course, very frustrating.

ZOË RUIZ: Throughout the book, you allow historical figures and histories long forgotten to come alive. I was fascinated by the historical figure Marie Equi. She was an “open” lesbian, physician, and local celebrity, who was tried and convicted and spent almost a year in prison at San Quentin. What were your first impressions of Marie Equi? Did those first impressions change or deepen throughout the research and writing process?

HEATHER MAYER: Marie Equi has always been a fascinating figure in local radical history, and she is finally getting the attention she deserves with the biography Michael Helquist has written about her for OSU Press. I think from what we know about Equi’s personal relationships she could be challenging to be around, quite temperamental. But the working people of Portland really seemed to love her--I think because of the care she provided, taking on patients who couldn’t pay and supplying birth control information and abortions when it was illegal to do so. She was more than just talk; she concretely helped people. And, she was never afraid to stand up for what she believed in, even at great personal risk.

CAROLYN SUPINKA: To end on, can you talk about how punk music introduced you to the history of radicalism?

HEATHER MAYER: Punk music has long been associated with politics but bands that I listened to in high school like Good Riddance and Propagandhi explicitly connected listeners to authors like Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn, the anarchist publisher AK Press, or included audio excerpts of famous speeches on their albums. In addition to the music I was listening to, I was a freshman in college when the 1999 WTO protests happened in Seattle, and that brought a lot of attention to the anarchist movement. I knew I wanted to study history, although I initially focused on Ancient Greek history. What was happening politically when I was in college really shifted my focus to radicalism, birth control activism, and anti-war activism, all movements that I then traced back to the early twentieth century.

***

Heather Mayer is a historian interested in social justice movements in the United States. Introduced to the history of radicalism through punk music and the antiglobalization and antiwar activism of the late 1990s and early 2000s, she decided to focus her studies on the intersections of gender and labor activism. She received her PhD from Simon Fraser University and has been teaching history at Portland Community College since 2008. She was born and raised in Oregon and lives with her family in the Portland area.