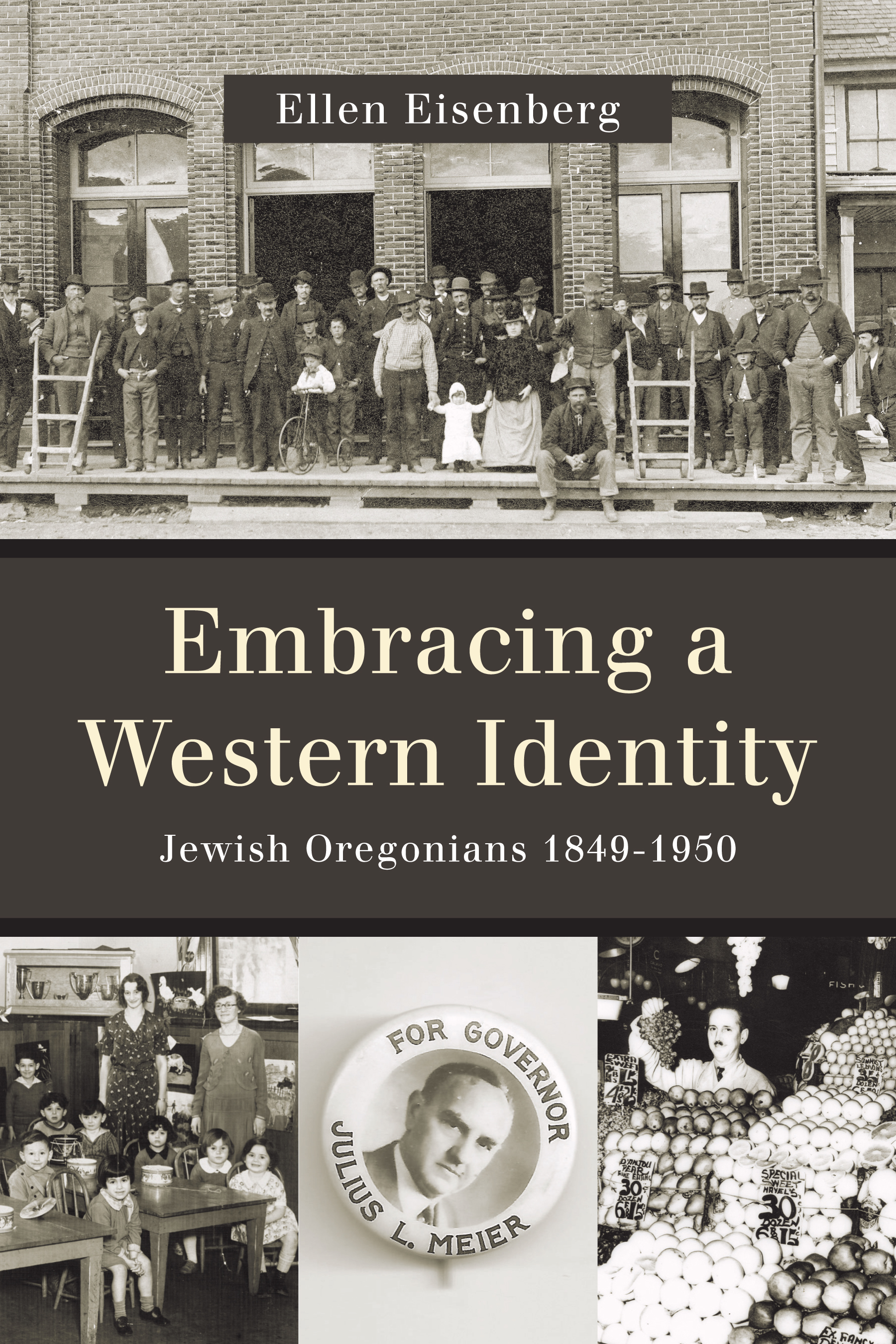

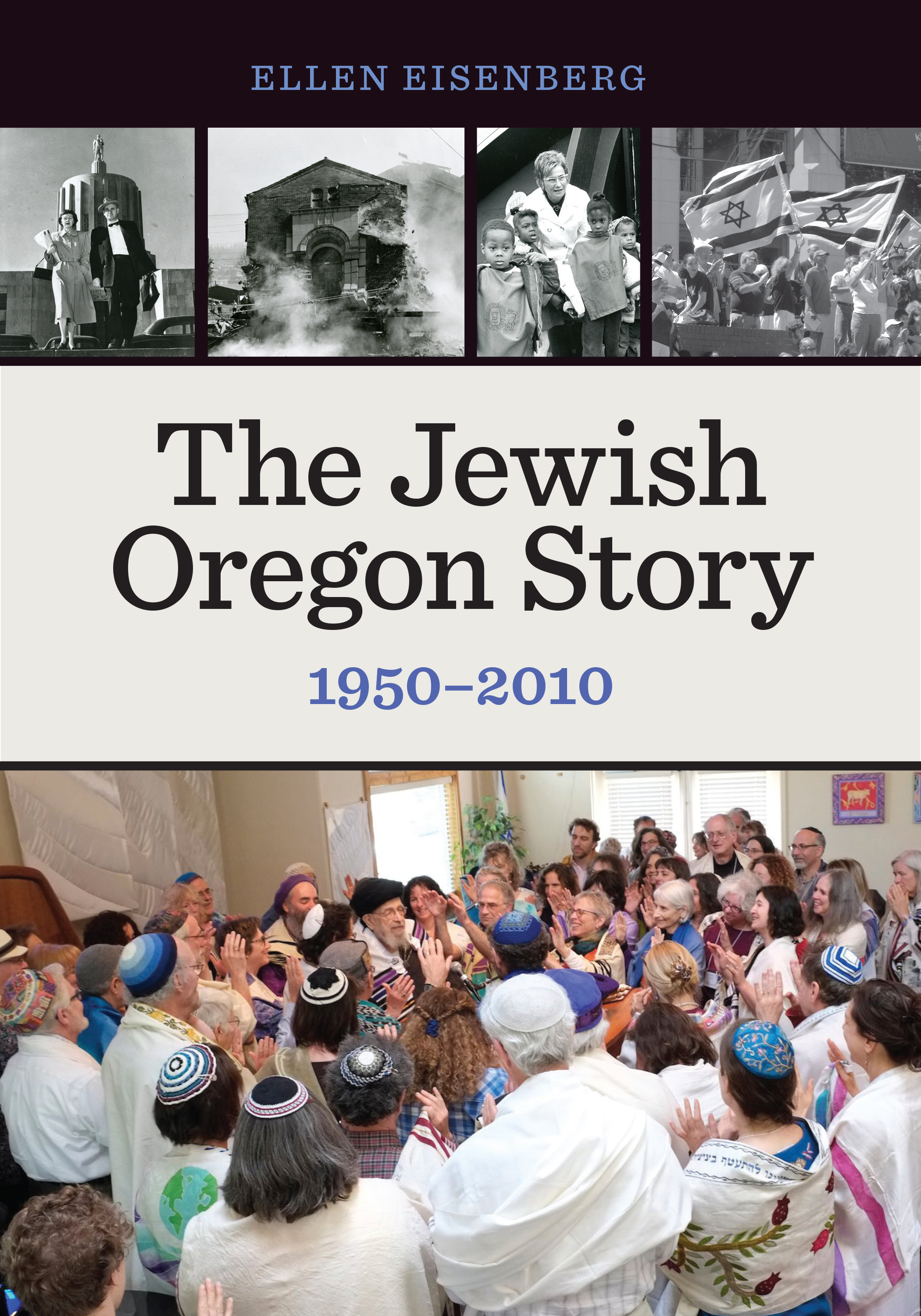

As Jews around the world celebrate Passover this week to commemorate their liberation from slavery in ancient Egypt, and with Holocaust Remembrance Day on April 12, the OSU Press would like to recognize the impact the Jewish community has had in the Pacific Northwest, and Oregon specifically. OSU Press author Ellen Eisenberg has spent her career working to research and recognize the oftentimes marginalized account of Jewish history in America. Her two most recent books Embracing a Western Identity: Jewish Oregonians 1849-1950 and The Jewish Oregon Story: 1950-2010 explore the ways Jews in the Pacific Northwest have symbiotically adapted to create a unique Jewish community in Oregon. Below is an except from Eisenberg’s “Introduction” to her first volume, Embracing a Western Identity, that articulates her initial interest in understanding the unique identity of the Jewish community in Oregon.

____________

Introduction

Like many western Jews, I am a transplant from the East. After a childhood in suburban Washington, DC, college in Minnesota, and graduate school in Philadelphia, I moved to Salem, Oregon in 1990. At the time, I had no intention of doing research on Oregon Jews—my dissertation focused on Jewish agricultural communities in New Jersey, and I was interested in comparative research on similar settlements in Argentina. Yet within a few years, I found myself increasingly intrigued by the Jewish history of my newly adopted state and region.

To be sure, shifting my research westward had practical benefits. Moving to Oregon with an infant in arms and having another child four years later provided a strong incentive to find projects that could be supported without prolonged trips away from home. Yet along with such pragmatic concerns, I was intrigued by a Jewish community that, while certainly not completely foreign, was noticeably different from those I had known back east. Part of this difference was simply a reflection of social differences between regions. I quickly learned that some Oregonians wear jeans and Birkenstocks (with socks) to synagogue services, just as they wear them to restaurants, meetings, and the theater.

Yet some differences seemed deeper. At a temple board retreat a few years after I arrived, all participants were asked to present a brief “Jewish autobiography.” I was surprised to learn that, of about a dozen participants, the rabbi and I were the only two in the room who were born Jewish and married to partners who were also born Jewish. I had grown up in a Conservative congregation where it seemed virtually all my peers shared a background roughly similar to mine—two Jewish parents from New York or some other eastern city and grandparents (possibly great-grandparents) who had immigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe. In Salem, the stories were far more diverse—converts, children of converts, children and grandchildren of immigrants who had settled in Colorado or Idaho or California rather than New York—as well as descendants of families who had been in America longer and come from a variety of places other than Eastern Europe.

Yet some differences seemed deeper. At a temple board retreat a few years after I arrived, all participants were asked to present a brief “Jewish autobiography.” I was surprised to learn that, of about a dozen participants, the rabbi and I were the only two in the room who were born Jewish and married to partners who were also born Jewish. I had grown up in a Conservative congregation where it seemed virtually all my peers shared a background roughly similar to mine—two Jewish parents from New York or some other eastern city and grandparents (possibly great-grandparents) who had immigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe. In Salem, the stories were far more diverse—converts, children of converts, children and grandchildren of immigrants who had settled in Colorado or Idaho or California rather than New York—as well as descendants of families who had been in America longer and come from a variety of places other than Eastern Europe.

Teaching immigration history at Willamette University and participating in the American Ethnic Studies program, I learned that the kinds of East/West differences I was observing were not confined to Jewish ethnic identity. European American ethnicities in general seemed blurrier in the West. Growing up in the East in the 1960s and 1970s, “ethnicity” had included many categories of European Americans; as kids, we were aware of one another’s ethnic past. It was not a major issue—there were no ethnic gangs in my suburban neighborhood—but there was an awareness of roots. Many families identified as Jewish or Italian or Irish or German American, and, although there were exceptions, most seemed to identify with just one of these identities. There was a set of ideas associated with each of these labels that included how many children the family was likely to have and what kinds of foods they were likely to eat. By the time we were in grade school we could easily sort surnames into the most common ethnic categories. The Goldsteins? Obviously, Jewish. The O’Shaughnessys? Clearly Irish. The D’Ambrosios? Italian. There were a few more recent Asian and Latino immigrant families, but in such small numbers that they didn’t seem to constitute a group, so conversations about ethnicity were far more likely to focus on European categories. And in suburban Washington, DC, in the 1960s and 1970s, the language of race tended to employ only two categories: black and white.

In contrast, I found that my (mostly) West Coast students have trouble thinking about ethnicity as a category they can apply to European Americans. When I talk with them about immigration, they think of Asians and Latinos, not Europeans. When I ask them about their family histories, the majority of those of European American origin are unable to point to one ethnic identity and instead present a laundry list—“my mom’s family is Norwegian, Swedish, Dutch, and French; my dad’s mom is Irish and his dad’s family is Scottish, German, and Russian.” Students in Willamette’s Jewish Student Union present “Jewish autobiographies” not unlike those I encountered at the board retreat—few were born to two Jewish parents and raised Jewishly. Far more come from families with diverse ancestry and a mix of traditions.

Not only do my western students of European descent not identify with a particular ethnic group, they also have little ability to recognize European ethnicity. When I talk in my American Jewish history class about a film or television character who, to me, seems obviously Jewish, I learn that a number of my students completely miss the identifiers. And, because they don’t speak the “language” of European ethnic identity, they frequently mistake non-Jewish New Yorkers for Jews. For years, my friend and colleague, Bill Smaldone—whose name is obviously identifiable to most easterners of my generation as Italian American—often has been misidentified by many of our students (and more than a few colleagues) as Jewish, based on his New York accent. They make the same mistake with the character George Costanza from Seinfeld (and Kramer and even Elaine, despite the shiksappeal episode).

In this, of course, students are reflecting not only a lack of familiarity with European American markers of ethnicity, but also a popular culture that has strongly identified Jews with New York—so much so that, for many of my students, to be a New Yorker is to be Jewish (at least if one is white). As Hasia Diner explains in her essay “American West, New York Jewish,” New York has been depicted as “the essence of what it means to be Jewish in America.” And New York is often juxtaposed in American culture with the West, identified as “that which has long been essentially America.” Diner argues that films such as Blazing Saddles (1974) and The Frisco Kid (1979) play on the contrast between that which is Jewish and “not quite America” and the “real” America that is the West. Thus, Jews—especially East European ones—are, quite literally (and often comedically) “out of place” in the American West, particularly the stereotypical, historic frontier West.

These patterns of ethnic understanding in popular culture mirror scholarship on ethnicity and the West. Over the last several decades, there has been a proliferation of work on western ethnicity and diversity in the wake of the New Western History. Yet in this scholarship, “ethnicity” and “diversity” nearly always denote non-European identities, and European immigrants have generally been neglected in western history. With the exception of Los Angeles, where a scholarship focusing on the interplay among a wide variety of groups including Latinos, Asian Americans, Jews, and other European Americans has emerged in the past several decades, much of the literature on ethnicity in the West focuses on non-Europeans, with Jews and other European immigrants simply categorized as “white.”

Such thinking is reinforced by scholarship on American Jewish history, which has focused heavily on New York as the mother lode of all that is Jewish in America. Reflecting the dominant place of New York Jewry in terms of community demographics, historians have often equated New York with American Jewry. Even locally produced western histories portray communities as a pale shadow of the “true” New York Jewish experience. Thus, community histories frequently compare “Jewish” neighborhoods such as Boyle Heights in Los Angeles, the Fillmore in San Francisco, South Portland, and Seattle’s Central District to the iconic Lower East Side. In The Jews of Oregon, Steven Lowenstein describes South Portland’s community as “largely self-contained,” “a separate community,” and explicitly links it to the Lower East Side of New York. Oral histories focusing on South Portland in the 1920s and 1930s describe a strong Jewish atmosphere, with frequent comparisons to the Lower East Side, and even some, however metaphorical, to a shtetl.

Despite the explicit or implicit connections in these descriptions to the landscape of the Lower East Side, Jewish communities in the region were profoundly shaped by the western experience, beginning with the distinctive migration pattern that brought Jews to the West. Whereas millions of Jews migrated directly from Europe to eastern ports, including New York, Boston, Baltimore, and Philadelphia; or immediately transmigrated to inland industrial centers such as Chicago, those who settled in the West arrived gradually and in far smaller numbers. This meant that, particularly before the turn of the century, even the largest western Jewish communities remained quite modest. As late as 1915, the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society of America reported that over 80 percent of immigrant Jews were bound for northern and central Atlantic states, and less than 1 percent for the West. Of those, only a fraction came to the Northwest. Those who came to Oregon were making a conscious choice to move outside the normal paths of Jewish life and into the American hinterland. They were attracted by opportunities that were shaped, in turn, by the distinctive environment, commercial prospects, and racial landscape of the region. The process of self-selection among migrants, combined with the particular opportunities and challenges of the region that they chose, shaped their experiences. They neither recreated the Lower East Side nor seamlessly blended into the local white landscape. Rather, they reflected both the Jewish and western forces that shaped them.

What began as curiosity about my new community and my students’ perceptions has led, over two decades, to a deep appreciation of the complex factors that have shaped Jewish history in the West, and, specifically, in Oregon. Along with my fellow historians of the Jewish experience in the American West, I have worked to break free of generalizations based on the eastern metropolitan experience that have ruled American Jewish history. Critical studies of Jewish life in the western states have delineated important points of contrast with eastern Jewry, such as the continued dominance of Jews of German descent into the twentieth century; the relative mildness of anti-Semitism; the declining Jewish percentage of the total western population at a time when the Jewish population share in the East was increasing rapidly; and the small numbers of East European migrants to the West and their correspondingly more modest impact on political and cultural developments. These contrasts have led historians to argue that concepts as basic as the customary periodization of American Jewish history do not apply to the American West. The challenges of the frontier, the particular mix of people who settled here, and the ethos they developed, along with the selective migration of Jews to this remote state have all contributed to the distinctive characteristics of Oregon Jewry. Yet Jewish Oregonians were also strongly shaped by the broader western and American Jewish communities of which they were a part.

What began as curiosity about my new community and my students’ perceptions has led, over two decades, to a deep appreciation of the complex factors that have shaped Jewish history in the West, and, specifically, in Oregon. Along with my fellow historians of the Jewish experience in the American West, I have worked to break free of generalizations based on the eastern metropolitan experience that have ruled American Jewish history. Critical studies of Jewish life in the western states have delineated important points of contrast with eastern Jewry, such as the continued dominance of Jews of German descent into the twentieth century; the relative mildness of anti-Semitism; the declining Jewish percentage of the total western population at a time when the Jewish population share in the East was increasing rapidly; and the small numbers of East European migrants to the West and their correspondingly more modest impact on political and cultural developments. These contrasts have led historians to argue that concepts as basic as the customary periodization of American Jewish history do not apply to the American West. The challenges of the frontier, the particular mix of people who settled here, and the ethos they developed, along with the selective migration of Jews to this remote state have all contributed to the distinctive characteristics of Oregon Jewry. Yet Jewish Oregonians were also strongly shaped by the broader western and American Jewish communities of which they were a part.

In discussing regional history, American Jewish historians have asked whether, for example, southern Jews have historically been more similar to other southerners or to non-southern Jews. In recent years, historians Mark Bauman and Marc Lee Raphael have come down on the side of the latter, arguing that, whatever regionalisms were embraced by southern Jews, “to a remarkable degree . . .their experiences were far more similar to those of Jews in similar environments elsewhere in America than they were to those of white Protestants in the South.” Part of this was due to the fact that, however well accepted and acculturated they were, there were some aspects of southern life that seemed incompatible with Jewish culture—indeed, “Southern Jewry” has been seen by some as a term that is “oxymoronic.” Yet, as Ava F. Kahn, William Toll, and I have argued in Jews of the Pacific Coast: Reinventing Community on America’s Edge, Jews found western civic culture and identity far more compatible with their Jewish identity than appears to have been the case in the South.

Embracing a Western Identity: Jewish Oregonians 1849-1950 enters this discussion of regional identity by focusing closely on the Jewish community of Oregon. The aim is to place Oregon Jewish history in the larger contexts of western and American Jewish histories through a series of essays, each focused on a particular theme, institution, or issue, to explore both the echoes of and the departures from the broader experience of Jews in the West, and in the United States.