Today press author Dr. Derek Larson joins us to discuss his book, Keeping Oregon Green. Larson guides us through the making of his book, including his inspirations and the influences in his life that led him to pursue this endeavor. Larson also provides us with an interview that was conducted just after the book’s release in November of 2016 by the Jefferson Public Radio, highlighting the environmental legacy built in Oregon “before green was cool.”

Click the link below to be directed to the Jefferson's Public Radio website to listen to Larson's interview.

http://ijpr.org/post/oregons-environmental-golden-age-remembered-new-book

---------------

It was hard to avoid environmental debates in Oregon in the 1970s. Even schoolchildren like myself were aware of looming threats to air and water quality, controversial efforts to preserve wilderness, and the obvious impacts of urban sprawl. When they showed a film called “Pollution in Paradise” in our classrooms, it made us worry about the future. But Oregon, we  quickly learned to our pride, was leading the nation in addressing the environmental crisis. We knew this from reading newspaper headlines, from the educational segments broadcast between cartoons on Saturday morning TV, and from parents who told us we were lucky to live in a state blessed with natural bounty and not yet overrun by concrete or choked by smog.

quickly learned to our pride, was leading the nation in addressing the environmental crisis. We knew this from reading newspaper headlines, from the educational segments broadcast between cartoons on Saturday morning TV, and from parents who told us we were lucky to live in a state blessed with natural bounty and not yet overrun by concrete or choked by smog.

It wasn’t until much later that I began to wonder what it was that made Oregonians take action to protect the environment when other states did not. What were the origins of the distinctive “Oregon way” I had witnessed as a child in the 1970s, when the state was routinely featured in the national media as a bellwether for environmental protection? The roots of my book Keeping Oregon Green began with this question and the answer turned out to be more complex than I’d initially imagined.

Environmental history and the history of the American West have been staples of my teaching since the late 1990s, which offered frequent opportunities to explore the broader context of Oregon’s environmental era. Summer and sabbatical travel offered time to dig into archival collections, to conduct interviews, and to explore the history of the national environmental awakening that culminated with the first Earth Day celebration in 1970. In the process it became clear that Oregon emerged as the national leader in environmental protection when it did for a number of reasons, not the least of which being rapid growth in the 1960s and its proximity to California’s famous smog, sprawl, and unplanned growth. But perhaps most important was the belief that Oregon had more to lose than other states, and thus its residents had greater reason to act.

Ultimately I decided to frame the book around the definitive victories of Oregon’s environmental revolution: the Beach Bill, the Bottle Bill, the revival of the Willamette River, and creation of the Land Conservation and Development Commission. To illustrate the pace of change I prefaced those events—all of which took place between roughly 1969-1974 –with a  study of the failed effort to establish a national park in the Oregon Dunes a decade earlier. Collectively the stories of these environmental conflicts tell us a great deal about what made Oregon different in the environmental era, why these advances were not easily replicated in other states at the time, and what it might ultimately take to build a strong political consensus around environmental protection again. Today Oregonians enjoy the benefits of advances made over forty years ago but the coalitions that made them possible have dissolved, leaving the state’s environmental future uncertain and its status as national leader resting more in its past than in its future promise. It was my hope that a deeper look at these once familiar stories might serve as a sort of orientation to younger and newer residents while helping anyone concerned to better understand “how things came to be this way” in Oregon and perhaps even how they might work together for a brighter—and greener –future.

study of the failed effort to establish a national park in the Oregon Dunes a decade earlier. Collectively the stories of these environmental conflicts tell us a great deal about what made Oregon different in the environmental era, why these advances were not easily replicated in other states at the time, and what it might ultimately take to build a strong political consensus around environmental protection again. Today Oregonians enjoy the benefits of advances made over forty years ago but the coalitions that made them possible have dissolved, leaving the state’s environmental future uncertain and its status as national leader resting more in its past than in its future promise. It was my hope that a deeper look at these once familiar stories might serve as a sort of orientation to younger and newer residents while helping anyone concerned to better understand “how things came to be this way” in Oregon and perhaps even how they might work together for a brighter—and greener –future.

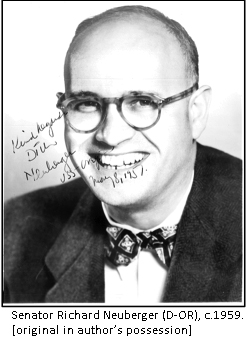

In the 1950s Oregon was just starting to show the impacts of its wartime industrial boom and post-war population growth. Political leaders were concerned more with economic growth and luring migrants into Oregon than about environmental quality. When Richard Neuberger, the state’s junior US Senator, began a push to have a second national park designated in Oregon  his approach was couched in pride as much as preservation: Oregon, he argued, deserved another national park. After all, both California and Washington had several, and their landscapes were no better than his state’s! Neuberger explored park possibilities in Hell’s Canyon and on Mount Hood, but quickly settled on the Oregon Dunes near Florence, one of the nation’s longest stretches of natural sand dunes and a relatively undeveloped area that was already partially managed by the U.S. Forest Service. Joining forces with Massachusetts senator John Kennedy and Texas senator Lyndon Johnson, Neuberger co-sponsored a bill that would create a new category of federal land called a “national seashore” under the aegis of the U.S. National Park Service. The ultimate failure of the bill despite Neuberger’s efforts to rally support for the park in Oregon illustrate a lack of widespread concern over environmental issues prior to the 1960s.

his approach was couched in pride as much as preservation: Oregon, he argued, deserved another national park. After all, both California and Washington had several, and their landscapes were no better than his state’s! Neuberger explored park possibilities in Hell’s Canyon and on Mount Hood, but quickly settled on the Oregon Dunes near Florence, one of the nation’s longest stretches of natural sand dunes and a relatively undeveloped area that was already partially managed by the U.S. Forest Service. Joining forces with Massachusetts senator John Kennedy and Texas senator Lyndon Johnson, Neuberger co-sponsored a bill that would create a new category of federal land called a “national seashore” under the aegis of the U.S. National Park Service. The ultimate failure of the bill despite Neuberger’s efforts to rally support for the park in Oregon illustrate a lack of widespread concern over environmental issues prior to the 1960s.

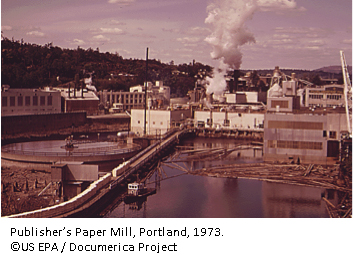

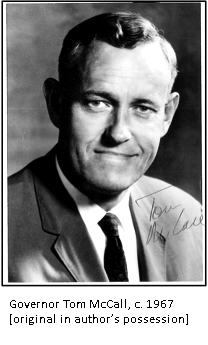

Things changed quickly soon after. The publication of Rachel Carson’s indictment of pesticides in the book Silent Spring rang an environmental alarm bell for the nation in 1962, coincidentally the same year a Portland news reporter named Tom McCall produced a television special called “Pollution in Paradise” for KGW-TV. McCall’s documentary awakened Oregonians to the reality of environmental decay in their midst: sewage-choked rivers, smoke-filled skies,  and escalating waste problems that belied the state’s reputation as a clean, uncrowded, natural paradise. Carson’s book is often credited as the launchpad of the American environmental movement, shifting attention from traditional conservation issues like parks and wilderness to quality of life concerns that impacted people where they lived. McCall’s local expose did the same for Oregon, while also raising his profile with the public; he was elected secretary of state in 1964 and governor in 1966. McCall’s political reputation would center around the environment more than any other issue.

and escalating waste problems that belied the state’s reputation as a clean, uncrowded, natural paradise. Carson’s book is often credited as the launchpad of the American environmental movement, shifting attention from traditional conservation issues like parks and wilderness to quality of life concerns that impacted people where they lived. McCall’s local expose did the same for Oregon, while also raising his profile with the public; he was elected secretary of state in 1964 and governor in 1966. McCall’s political reputation would center around the environment more than any other issue.

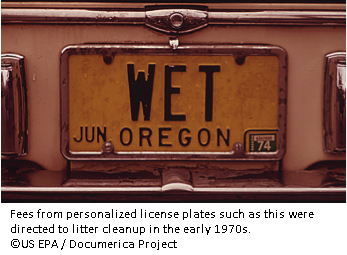

During two terms in office—serving from 1967 through 1975 –Tom McCall helped lead Oregon to national prominence in the environmental arena. Pledging upon his first election to clean up the fetid Willamette River, he oversaw a public campaign to reduce the flow of industrial and  municipal waste that culminated in a National Geographic cover story in 1972 headlined “A River Reborn.” Campaigns to reduce litter by targeting disposable beverage containers and to secure the state’s beaches for public access also drew national attention, as Oregon became the national leader in progressive environmental legislation and McCall became the nation’s “environmental governor.” At the outset of his second term in office McCall charged the legislature with its biggest task yet: developing a plan to manage growth in the future so Oregon did not end up like California, which he often used as rhetorical shorthand for the collective ills of unmanaged population growth and environmental decline. The result—the Land Conservation and Development Commission –remains the nation’s most successful and studied land use planning system, as well as one of its most controversial.

municipal waste that culminated in a National Geographic cover story in 1972 headlined “A River Reborn.” Campaigns to reduce litter by targeting disposable beverage containers and to secure the state’s beaches for public access also drew national attention, as Oregon became the national leader in progressive environmental legislation and McCall became the nation’s “environmental governor.” At the outset of his second term in office McCall charged the legislature with its biggest task yet: developing a plan to manage growth in the future so Oregon did not end up like California, which he often used as rhetorical shorthand for the collective ills of unmanaged population growth and environmental decline. The result—the Land Conservation and Development Commission –remains the nation’s most successful and studied land use planning system, as well as one of its most controversial.

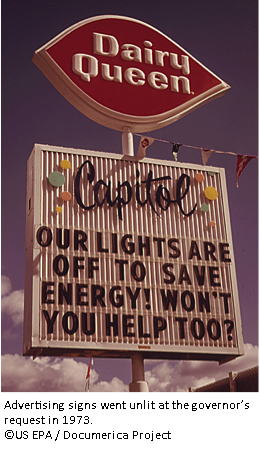

At the heart of Keeping Oregon Green are the stories behind these environmental advances. The laws themselves are important, both for their impact within the state and as national models. But more interesting  to me is the cultural context in which these political acts were fashioned. Once awakened to the declining quality of their environment, Oregonians of varied political backgrounds collectively called for change. Their state, it was thought, was special. It was their duty to protect it, both for future generations and out of respect for their forbearers. Allowing it to be consumed by litter, clogged with sewage, and choked with smoke was simply unacceptable. The arguments they made, be they within the halls of the state capitol, on the editorial pages of the region’s newspapers, or in letters written to Governor McCall, were most often framed in personal terms and expressed concerns about specific places that were important to them as individuals or families. When the governor called for sacrifice, as during the 1973 energy crisis, most people willingly complied. This collective sense of place was a powerful weapon against environmental decay, one that bridged other differences and helped produce a consensus in support of actions that would have been inconceivable in many other parts of the country then or now.

to me is the cultural context in which these political acts were fashioned. Once awakened to the declining quality of their environment, Oregonians of varied political backgrounds collectively called for change. Their state, it was thought, was special. It was their duty to protect it, both for future generations and out of respect for their forbearers. Allowing it to be consumed by litter, clogged with sewage, and choked with smoke was simply unacceptable. The arguments they made, be they within the halls of the state capitol, on the editorial pages of the region’s newspapers, or in letters written to Governor McCall, were most often framed in personal terms and expressed concerns about specific places that were important to them as individuals or families. When the governor called for sacrifice, as during the 1973 energy crisis, most people willingly complied. This collective sense of place was a powerful weapon against environmental decay, one that bridged other differences and helped produce a consensus in support of actions that would have been inconceivable in many other parts of the country then or now.

Those of us who were in Oregon in the 1970s likely remember many of the changes wrought as a result. We started picking u p bottles and cans along the roadsides and returning them to stores for pocket change. We walked the sandy beaches of the Oregon Coast secure in the knowledge that nobody could fence us out or proclaim part of “our” beach to be private. We watched the wigwam burners go dark and their smoke drift away for the last time, smelled the fresher air in towns with paper mills, and watched the salmon return to the Willamette. Even more important is what we didn’t see: Oregon did not plow under its farms for subdivisions, nor pave its forests for highways. While growth did come, it came in a managed fashion that helped keep Oregon green. All of these things are the legacy of a relatively short period of time and a remarkable series of political (and cultural) events that made Oregon the envy of the nation’s environmental advocates and at times the bane of the “growth at any cost” crowd who would put economics before all else. Through exploring the stories behind these events and their broader context I was finally able to answer the questions I raised years ago—why Oregon? why then? –while also gaining some insight into what might be required to address some of the environmental challenges we’ll face in the 21st century. Keeping Oregon Green, in the end, is an ongoing project that requires renewed dedication with each generation. The stories of Oregon’s first environmental era should serve simultaneously as inspiration and warning: quality of life in the region is high but it will take significant commitment to keep it that way in the future.

p bottles and cans along the roadsides and returning them to stores for pocket change. We walked the sandy beaches of the Oregon Coast secure in the knowledge that nobody could fence us out or proclaim part of “our” beach to be private. We watched the wigwam burners go dark and their smoke drift away for the last time, smelled the fresher air in towns with paper mills, and watched the salmon return to the Willamette. Even more important is what we didn’t see: Oregon did not plow under its farms for subdivisions, nor pave its forests for highways. While growth did come, it came in a managed fashion that helped keep Oregon green. All of these things are the legacy of a relatively short period of time and a remarkable series of political (and cultural) events that made Oregon the envy of the nation’s environmental advocates and at times the bane of the “growth at any cost” crowd who would put economics before all else. Through exploring the stories behind these events and their broader context I was finally able to answer the questions I raised years ago—why Oregon? why then? –while also gaining some insight into what might be required to address some of the environmental challenges we’ll face in the 21st century. Keeping Oregon Green, in the end, is an ongoing project that requires renewed dedication with each generation. The stories of Oregon’s first environmental era should serve simultaneously as inspiration and warning: quality of life in the region is high but it will take significant commitment to keep it that way in the future.

Related Titles

Keeping Oregon Green

Keeping Oregon Green is a new history of the signature accomplishments of Oregon’s environmental era: the revitalization of the polluted Willamette River, the Beach Bill...